Tied with Chelsea as the first porcelain factory in England, Bow was famous for its industrious output and development of fine bone china. Inspired by the exported goods from Asia, which had been competition for British craftsmen since the 17th century, Bow set about creating its own designs as well as directly copying those from China, Japan and the rest of the world. By the mid 18th century, they opened the largest porcelain manufactory in the country, naming it New Canton.

Above: a selection of porcelain produced by Bow in the 18th century including plates, figurines and vases

Above: a selection of porcelain produced by Bow in the 18th century including plates, figurines and vases

Not only was New Canton named after the thriving port of origin for many Chinese goods, but the facade of the building was a direct copy of the East India Warehouse based in Canton. The aims of Bow could not be clearer and would prove to be a commercial success. This article will explore the history, materials and identification of Bow porcelain, as well as the restoration of two figurines for Newham Borough Council.

Above: items from the Bow porcelain works including a parrot figurine (1760), a Famille Rose style covered vase (1748-1750) and commedia dell’arte figurines after Antoine Watteau (1748)

Above: items from the Bow porcelain works including a parrot figurine (1760), a Famille Rose style covered vase (1748-1750) and commedia dell’arte figurines after Antoine Watteau (1748)

History

The story of Bow begins in the 1740s, when Edward Heylyn and Thomas Frye obtained a patent for the creation of porcelain goods. Although their business was named after the area of Bow in East London, the original factory was set up in West Ham, Essex. Ideally situated close to the River Lea, the Bow factory had easy access to raw materials being shipped to them as far as the American colonies.

Above: two Bow figurines inspired by other European factories (1760) and a plate copied from an Asian design (1755)

Above: two Bow figurines inspired by other European factories (1760) and a plate copied from an Asian design (1755)

Prior to the Meissen factory having its arcanum for hard paste porcelain leaked to European manufacturers, experiments in the field of ceramics lead to the development of a soft paste alternative. This was not as strong as the products from Asia, but nonetheless achieved a very similar aesthetic. Bow was the first to implement soft paste porcelain commercially, at the very same time as the Chelsea factory located in the west of London.

Above: a selection of white items from the Bow factory, including figurines of Henry Woodward and Kitty Clive – two of the earliest examples of full figures in English porcelain

Above: a selection of white items from the Bow factory, including figurines of Henry Woodward and Kitty Clive – two of the earliest examples of full figures in English porcelain

The artistic aims of the Bow factory were focused on the imitation of popular porcelain goods and fashionable styles. This included the direct copy of tableware and decorations from China and Japan, as well as figures from Meissen and even rivals in the UK. By the 1760s, Bow was employing upwards of 300 people – including 90 painters – making it the largest porcelain manufacturer in the country.

Above: details of the paintwork on Bow figurines including the Laotian goddess Ki Mao Sao (1750-52), a seated musician (1765) and a lady from a pair called ‘The Thrown Kiss’ (1765) and an allegory of Earth (1755)

Above: details of the paintwork on Bow figurines including the Laotian goddess Ki Mao Sao (1750-52), a seated musician (1765) and a lady from a pair called ‘The Thrown Kiss’ (1765) and an allegory of Earth (1755)

The ceramics developed at Bow include the earliest form of fine bone china – named after the animal ash that gave the products extra strength in the kiln. As the bone ash was likely to have been sourced from a local farm, it was an economical move as well as a practical achievement in their rapid manufacturing.

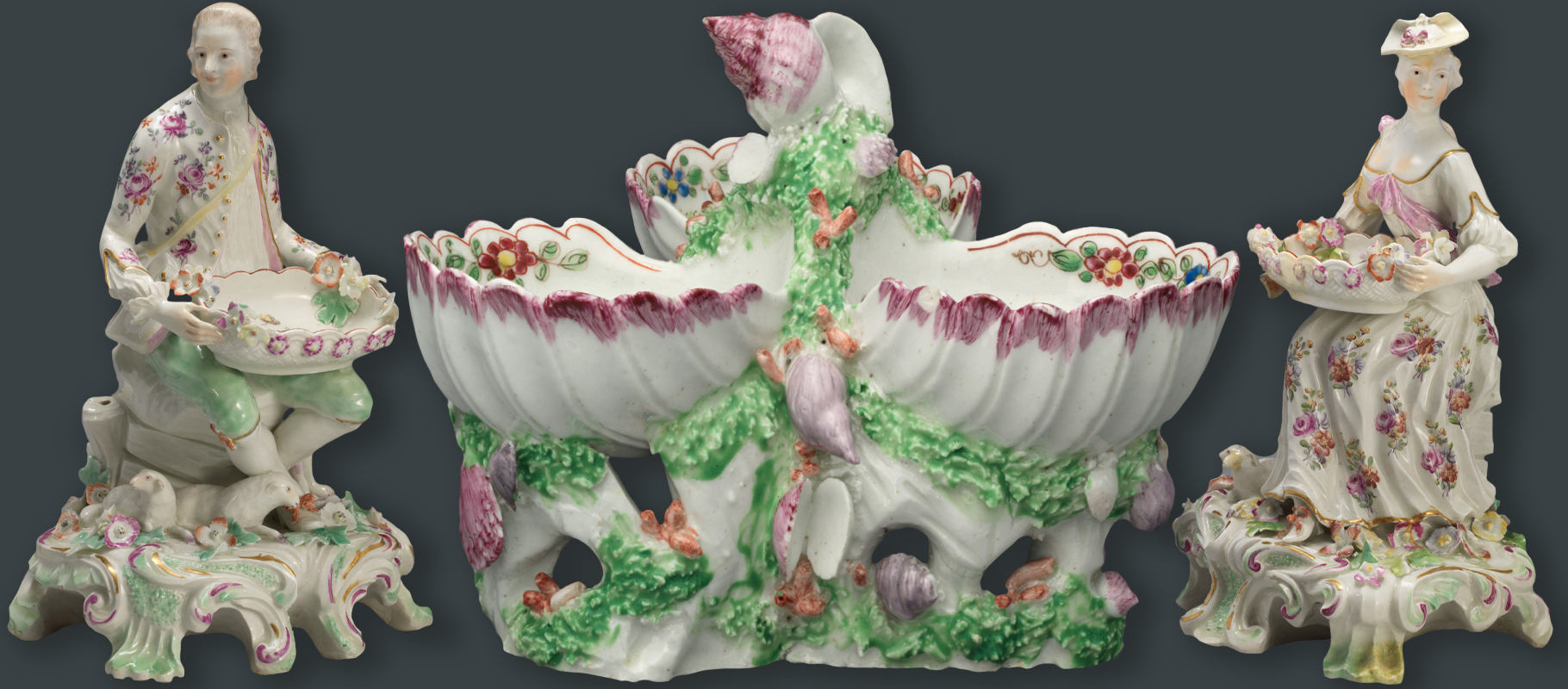

Above: a pair of Bow figurines (1760-65) and a sweetmeat dish (1750)

Above: a pair of Bow figurines (1760-65) and a sweetmeat dish (1750)

By the 1770s, the factory was reaching the end of its short production history as it was taken over by various competitors and eventually closed in 1776. The success of the New Canton factory and its limited run of manufacturing makes Bow porcelain a rare and much sought after make of antique porcelain today.

Above: a pair of Bow porcelain busts (1750) and green parrots in a tree (1755-60)

Above: a pair of Bow porcelain busts (1750) and green parrots in a tree (1755-60)

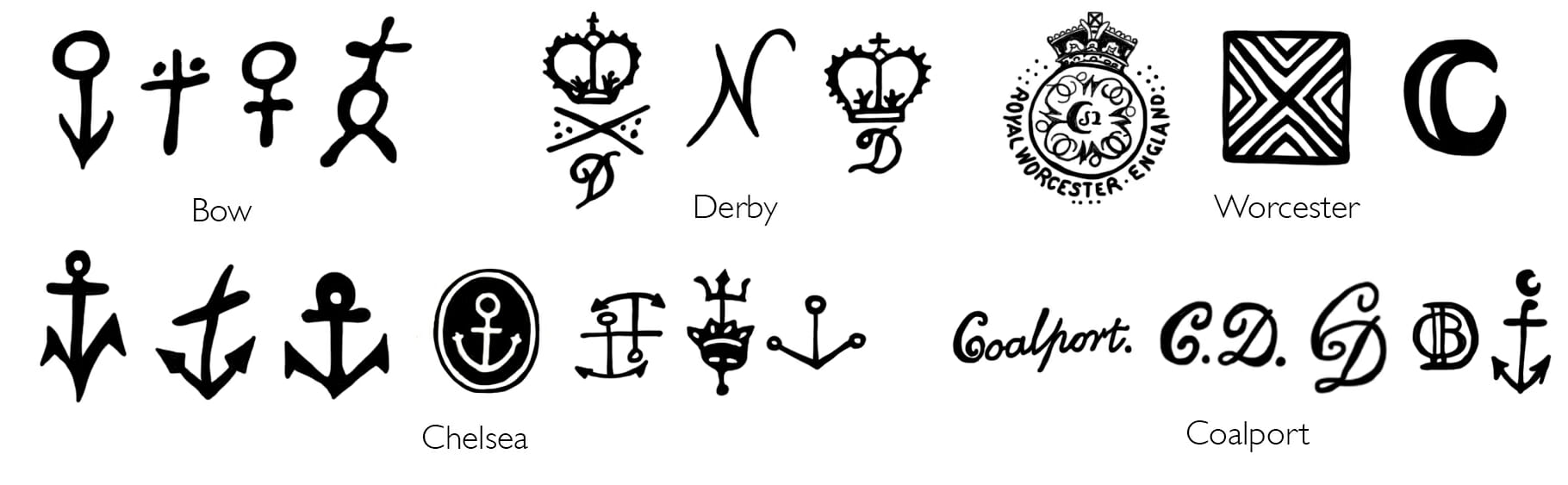

Identification and Bow maker’s marks

Typical signs of bow porcelain include a thickness to the ceramic body as a result of many designs being pressed into a mould by hand rather than the slip technique used by other factories. The ceramics may appear to be under-fired to prevent the deformities, often creating issues in the production of soft paste porcelain. A thick appearance is often a telling sign of Bow if it is held up to light, with only the edges appearing translucent.

Above: an original Chinese plate produced for the British market (1723-35) and a Bow copy of the same ‘famille rose’ design

Above: an original Chinese plate produced for the British market (1723-35) and a Bow copy of the same ‘famille rose’ design

Copies of original Chinese designs may appear a little clumsy when compared with the originals and sometimes more commercial in their approach, going as far to imitate Chinese and Japanese words and markings without knowledge of the original meaning or structure of the letters. The Bow example above is from 1755 and has several differences when up against the Chinese plate from 1723-35.

Early pieces of Bow are unlikely to have maker’s marks as it was not yet a common practice. Marks that have been discovered include an anchor, a circle with an arrow and a crescent moon.

Bow figurines usually have a rococo style scrolled base with four feet. Another telling feature is a square hole in the back, presumably for a metal candlestick holder to be inserted. You may recognise the design from another maker of the same period, but this is not a negative – it is often because all of the factories were taking inspiration from each other to reach commercial success.

Above: the base of a Bow porcelain sweetmeat dish, 1760

Above: the base of a Bow porcelain sweetmeat dish, 1760

Bow porcelain value

Today, items connected to the Bow porcelain works can fetch anywhere between £500 to £45,000 at auction. The result depends on the rarity, condition and the enthusiasm of collectors in the room. Some of the highest results have been in the United States. At Sotheby’s New York in 2011, a pair of Bow peasants dated to 1755-60 sold for $25,000. At the estate sale of Mrs. Charles W. Engelhard in 2005, a pair of bow owls reached an astonishing price of $228,000. More recently in 2018, a pair of duck shaped trinket boxes sold for $35,000, far surpassing their estimate of $12,000 to $18,000.

Above: a pair of Bow porcelain duck boxes, similar to the ones that sold for $35,000 in 2018

Above: a pair of Bow porcelain duck boxes, similar to the ones that sold for $35,000 in 2018

Restoring a pair of Bow porcelain figurines for Newham Borough Council

Earlier this year our team was contacted by the London Borough of Newham, the authority covering the area that would have historically been home to the Bow porcelain factory and their craftsmen. Two figurines had become accidentally damaged and required a conservation approach to appropriately restore the breakages. These were not only valuable pieces of Bow porcelain but important items in the London Borough’s cultural heritage.

The figurines have a pastoral theme, typical to the mid 18th century through the rococo movement. Intended to be displayed as a pair, the figures are of a shepherd and shepherdess. Their forms are closely related to several sets of Meissen figurines, although the shepherdess is holding a posy of flowers rather than a flute to match her pipe playing partner. Other English porcelain works of the period had their own take on this idyllic pairing. It was attractive to aristocratic patrons who had a romanticised view of an unrestricted life in the countryside – a utopian landscape often referred to as Arcadia.

Above: porcelain figurines with a pastoral theme from various makers around Europe in the 18th century

Above: porcelain figurines with a pastoral theme from various makers around Europe in the 18th century

During the 1740s, French court painter François Boucher was well known for artworks reflecting this sense of pastoral bliss, his designs were often copied into figurines by Meissen and other European factories. A Boucher painting entitled ‘Shepherd Piping to a Shepherdess’ was composed around 1747-1750 and is now housed in The Wallace Collection. This painting is said to have been inspired by a Charles Simon Favart play from 1745 called ‘The Harvest in the Vale of Tempé’. A similar pastoral comedy was written by Scottish playwright Allan Ramsay in 1725, entitled The Gentle Shepherd. Theatrical success may also be the source of popularity behind these porcelain decorations.

Above: a detail from The Interrupted Sleep by François Boucher, 1750

Above: a detail from The Interrupted Sleep by François Boucher, 1750

The first stage in the conservation process was to sensitively clean all of the surfaces, no matter how small the fragments were. This ensured that there was no build up of historic contamination or dust. The broken pieces were then prepared for bonding, behind being gently re-attached using a non acidic adhesive. The non acidic adhesive is important, as it is not known to yellow in the same way that household super-glues and tape would, it will also not cause further damage with unnecessary chemicals.

Following the reconstruction of the figurines, cracked and disturbed areas were filled or recreated with a conservation-appropriate material, before being retouched to match the colour and texture of the original porcelain. The result allows for a near seamless repair, allowing the figurines to be saved without disturbing their historic integrity. The results ensured that the pair could return to Newham and continue to be appreciated by future generations.

How can we help?

If you have any questions about restoration, please do not hesitate to get in touch. As part of our service we offer a nationwide collection and delivery service. E-mail us via [email protected] or call 0207 112 7576 for more information.

Above: a selection of porcelain produced by Bow in the 18th century including plates, figurines and vases

Above: a selection of porcelain produced by Bow in the 18th century including plates, figurines and vases Above: items from the Bow porcelain works including a parrot figurine (1760), a Famille Rose style covered vase (1748-1750) and commedia dell’arte figurines after Antoine Watteau (1748)

Above: items from the Bow porcelain works including a parrot figurine (1760), a Famille Rose style covered vase (1748-1750) and commedia dell’arte figurines after Antoine Watteau (1748) Above: two Bow figurines inspired by other European factories (1760) and a plate copied from an Asian design (1755)

Above: two Bow figurines inspired by other European factories (1760) and a plate copied from an Asian design (1755) Above: a selection of white items from the Bow factory, including figurines of Henry Woodward and Kitty Clive – two of the earliest examples of full figures in English porcelain

Above: a selection of white items from the Bow factory, including figurines of Henry Woodward and Kitty Clive – two of the earliest examples of full figures in English porcelain Above: details of the paintwork on Bow figurines including the Laotian goddess Ki Mao Sao (1750-52), a seated musician (1765) and a lady from a pair called ‘The Thrown Kiss’ (1765) and an allegory of Earth (1755)

Above: details of the paintwork on Bow figurines including the Laotian goddess Ki Mao Sao (1750-52), a seated musician (1765) and a lady from a pair called ‘The Thrown Kiss’ (1765) and an allegory of Earth (1755) Above: a pair of Bow figurines (1760-65) and a sweetmeat dish (1750)

Above: a pair of Bow figurines (1760-65) and a sweetmeat dish (1750) Above: a pair of Bow porcelain busts (1750) and green parrots in a tree (1755-60)

Above: a pair of Bow porcelain busts (1750) and green parrots in a tree (1755-60) Above: an original Chinese plate produced for the British market (1723-35) and a Bow copy of the same ‘famille rose’ design

Above: an original Chinese plate produced for the British market (1723-35) and a Bow copy of the same ‘famille rose’ design

Above: the base of a Bow porcelain sweetmeat dish, 1760

Above: the base of a Bow porcelain sweetmeat dish, 1760 Above: a pair of Bow porcelain duck boxes, similar to the ones that sold for $35,000 in 2018

Above: a pair of Bow porcelain duck boxes, similar to the ones that sold for $35,000 in 2018 Above: porcelain figurines with a pastoral theme from various makers around Europe in the 18th century

Above: porcelain figurines with a pastoral theme from various makers around Europe in the 18th century Above: a detail from The Interrupted Sleep by François Boucher, 1750

Above: a detail from The Interrupted Sleep by François Boucher, 1750