From printmaking to freehand sketches, ink has always played an important role. Whether it is applied in preliminary drawings or used as the final medium, it is found in many forms – each with their own unique colour and origin.

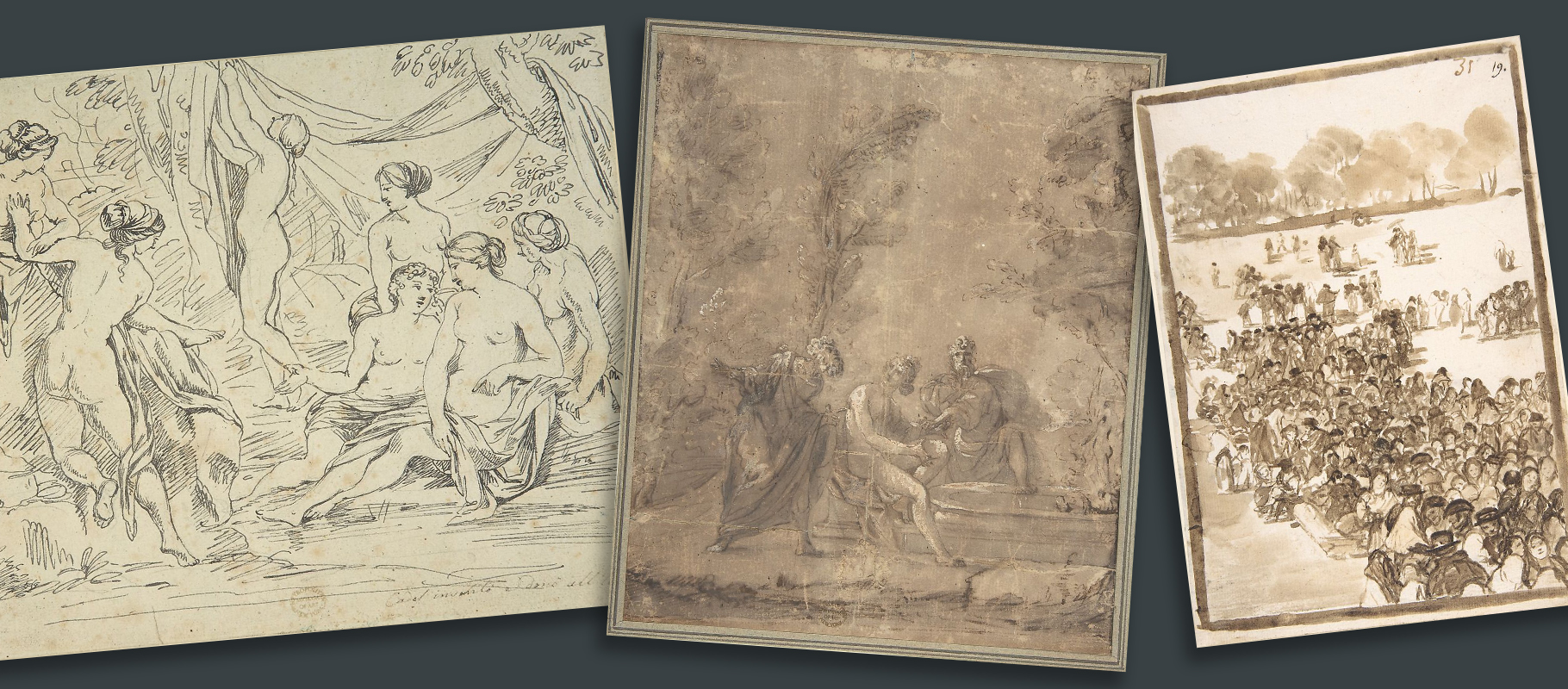

Above: a variety of ink drawings from the renaissance to the 19th century

Above: a variety of ink drawings from the renaissance to the 19th century

This article will explore the numerous tones and styles of ink found across the history of art. We will also offer advice on how to care for ink artworks at home, including appropriate conservation techniques and treatments available from our skilled team.

Above: a variety of ink drawings from the renaissance to the 19th century

Above: a variety of ink drawings from the renaissance to the 19th century

Ink composition and materials

Historically, ink has been applied in a variety of water-based solutions and pastes. The result differs due to the ingredients and tools. Early artists may have used hand-cut reeds and quills made of hollow flight-feathers. In the early 19th century, a more uniform fountain pen was patented, making it an popular tool by the advent of the industrial era.

Above: a pen from ancient Rome, Ming dynasty writing brush with lid, 16th century goose feather pen, 19th century silver tipped quill, and a late 18th century pen case

Above: a pen from ancient Rome, Ming dynasty writing brush with lid, 16th century goose feather pen, 19th century silver tipped quill, and a late 18th century pen case

Depending on the source of the ink, the colour may appear in a wide range of shades due to the style of application and the organic substance used. Historic ink may dry and age into a reddish brown or sepia appearance. Whilst most artists would have expected the tone of the final result, others may have never witnessed the eventual colour of their work.

Above: detail from a pen and wash drawing of Bacchus and Ariadne by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, 1740

Above: detail from a pen and wash drawing of Bacchus and Ariadne by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, 1740

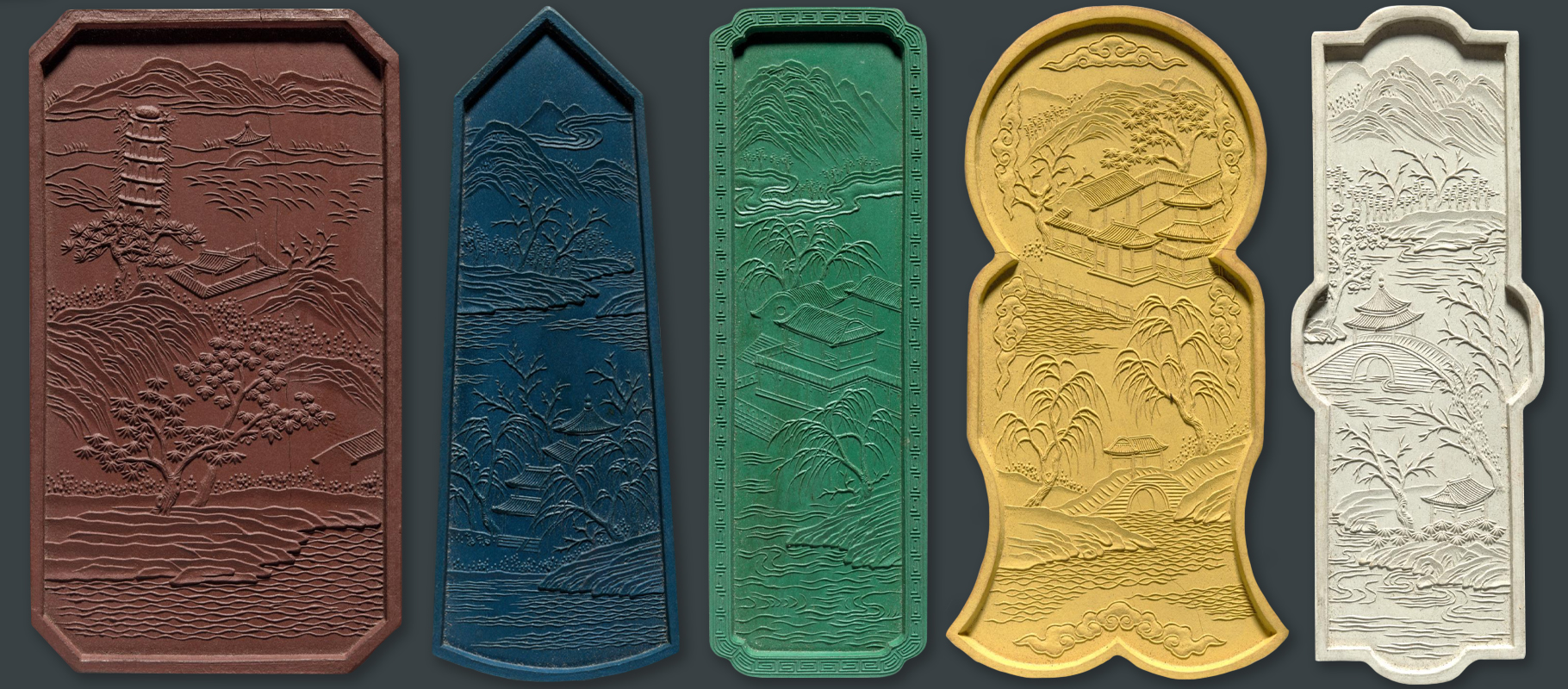

Sources of ink often vary depending on what was accessible to the artist. The most common forms derive from soot, carbon, oak gall nuts, and cuttlefish, mixed with gum arabic, glue or a liquid to make it malleable. To mask the smell of animal glue derived from fish, egg white and bone, incense may have also been included.

Above: a set of Qing dynasty ink cakes, 1780-94

Above: a set of Qing dynasty ink cakes, 1780-94

Easily obtainable substances would have been mixed by hand, ‘bistre ink’ soot would have been sourced from fireplaces whilst ‘lamp black’ carbon was created by burning an oil or resin. Powdered pigments and pre-mixed ink purchased from chemists or colourmen were commonly the oak iron gall variety. Early inks tend to include a lot of sediment and may easily clog or corrode a fountain pen. This encouraged modern varieties to use synthetic materials or a more easily manufactured logwood.

Above: detail from Studies of a Woman Wearing an Elaborate Headdress by an anonymous artist, retouched by Peter Paul Rubens, 1500

Above: detail from Studies of a Woman Wearing an Elaborate Headdress by an anonymous artist, retouched by Peter Paul Rubens, 1500

Each variety of ink has its own structure, historic impact and conservation concerns. Below are some of the most common forms of ink found across art history.

Carbon Ink Drawings

Black ink is traditionally produced from carbon, often a soot residue left by oil, bone, plants or resin following their use as fuel in a fireplace or lamp. Lamp Black, as its name suggests, was sourced from the soot of a household lamp. The burnt remains of oil or pine resin were a stable and highly pigmented base for artistic application. When Lamp Black is diluted with water, gum or animal glue it may be referred to as India Ink.

Above: Saint Clement by Andrea Lilio (1570-1630), Goats by Nicolaes Berchem (17th century), Battle of the Milvian Bridge by Johann Heintz (1612), Florence Leyland by James McNeill Whistler (1874) and Design for Emblematic Frontispiece “Natura Ars Emula Vincit” by Circle of Giovanni Guerra (1544-1618)

Above: Saint Clement by Andrea Lilio (1570-1630), Goats by Nicolaes Berchem (17th century), Battle of the Milvian Bridge by Johann Heintz (1612), Florence Leyland by James McNeill Whistler (1874) and Design for Emblematic Frontispiece “Natura Ars Emula Vincit” by Circle of Giovanni Guerra (1544-1618)

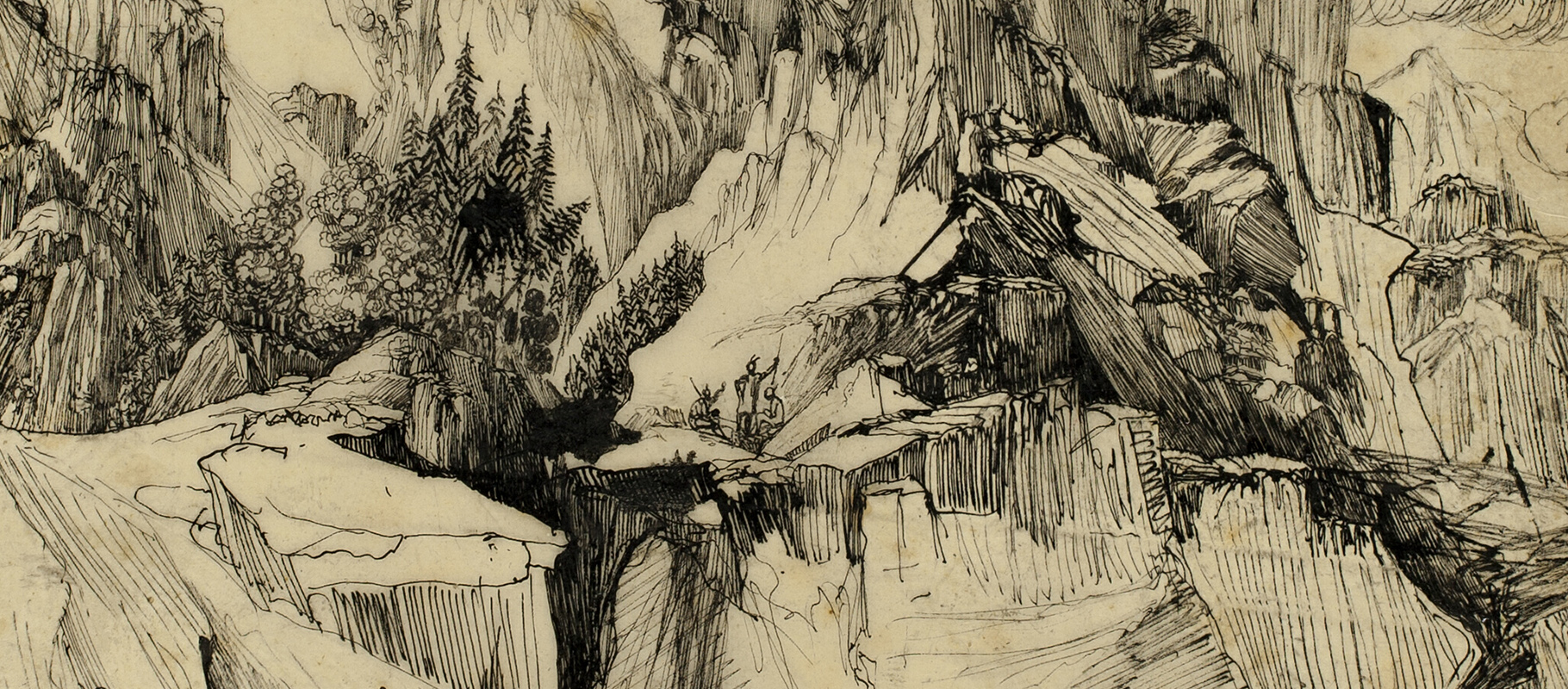

Although the ink has Asian origins, India Ink was produced across Europe from the 12th century onwards. Lamp Black may also be toned down to a grey wash when it is diluted, allowing the artist to create effective shades from one easily obtainable substance.

Above: detail from The Crevasse by Rodolphe Bresdin, 1860

Above: detail from The Crevasse by Rodolphe Bresdin, 1860

Ivory Black and Vine Black are also found in carbon-based ink. Ivory Black is obtained from bone char, whilst Vine Black was historically produced from the burnt remains of grape plants. All of these varieties have a slightly different tone to them and therefore are favoured by artists for different purposes. Ivory Black, for example, has a warm brown undertone, whilst Vine Black has more of a cool blue tone. Lamp Black is the boldest shade, but also hints towards blue.

Above: black ink drawings by Titian, Goya and Daumier

Above: black ink drawings by Titian, Goya and Daumier

The pure carbon base of this ink means that it is unlikely to fade, however over-application may cause a thick layer of ink to flake off. India Ink is also unlikely to disturb or corrode the paper it is applied on. However, precautions should still be taken to protect the drawing, writing or print from airborne residues, foxing, moisture and acidic framing materials.

Above: study for The Departure of Jacob by François Boucher (1755), an Allegorical Figure (16th century) and an illustration for A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Arthur Rackham (1908)

Above: study for The Departure of Jacob by François Boucher (1755), an Allegorical Figure (16th century) and an illustration for A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Arthur Rackham (1908)

Sepia Ink Drawings

A well-known shade of warm brown, Sepia Ink is used in a linear form as well as a wash. Although the tone is familiar throughout art history, often due to the faded colour of older ink varieties, true Sepia Ink was not used by artists until the early 19th century. This may be due to the complex cultivation of the source – cuttlefish. Usually produced in a hot climate, Sepia Ink is created by leaving cuttlefish outside to dry in the sun. The ink sacs are taken out, boiled, mixed with potash or soda, and filtered.

Above: two ‘sepia’ drawings – The Actor Clairval by Étienne Aubry (18th century) and Landscape with Sheep by Claude Lorrain (1648)

Above: two ‘sepia’ drawings – The Actor Clairval by Étienne Aubry (18th century) and Landscape with Sheep by Claude Lorrain (1648)

Today, many drawings are referred to as being ‘sepia’ whether or not they are truly derived from cuttlefish ink. True sepia ink and any ‘sepia’ style ink should be displayed behind UV protective glazing to prevent loss of colour.

Above: a detail from a preparatory ‘sepia’ study for Perseus and the Origin of Coral by Claude Lorrain, 1671

Above: a detail from a preparatory ‘sepia’ study for Perseus and the Origin of Coral by Claude Lorrain, 1671

Bistre Ink Drawings

Bistre is taken from the residue found in chimney stacks and has a tar-like appearance. Artists would have created Bistre Ink themselves by scraping their fireplace and filtering out the larger particles. They would then burn the mixture to dilute it to a usable consistency along with a gum to bind and thicken.

Above: a selection of bistre ink drawings

Above: a selection of bistre ink drawings

The appearance of Bistre Ink can range from cool to warm brown. It was also used in watercolours as well as pen-based applications. Bistre Ink can be seen in ink sketches by Rembrandt and is associated with many Old Master drawings.

Above: detail from a pen and bistre drawing of Moses Trampling on Pharaoh’s Crown, 18th century

Above: detail from a pen and bistre drawing of Moses Trampling on Pharaoh’s Crown, 18th century

Depending on the thickness of the artist’s mixture, Bistre Ink may sit on top of paper, making it vulnerable to surface deterioration. Unlike Lamp Black and other carbon inks, Bistre will fade when exposed to UV light and must be safely displayed behind specialist glazing to prevent loss. It should not be displayed in a bright environment, a maximum of 50 LUX is recommended to ensure preservation.

Above: three drawings completed with pen and bistre

Above: three drawings completed with pen and bistre

Iron Gall Ink Drawings

Created from a mixture of tannic acid and iron, Iron Gall Ink was famously used to compose the earliest example of the bible, Codex Sinaiticus. Due to easily obtainable materials, it remained a popular style of ink composition from the 12th century until the chemical industrialisation of the 20th century.

Above: examples of iron gall ink including a design by Jacopo della Quercia (1415-16), study of a nude by Francesco Salviati (1526-27) and a drawing by Jean-François Millet (1830-75)

Above: examples of iron gall ink including a design by Jacopo della Quercia (1415-16), study of a nude by Francesco Salviati (1526-27) and a drawing by Jean-François Millet (1830-75)

The ink tannins are derived from gall nuts, a botanical growth caused by insect larvae – sometimes referred to as an oak apple. When it is first applied, the ink appears almost clear and sinks into the paper. As it dries, the ink reacts with oxygen and darkens into a bolder form. As a result of this, Iron Gall Ink is difficult to erase and more hardy than other historic varieties. Although the ink appearances close to black, it can age into a rusty brown tone.

Above: a 17th century drawing with classic signs of severe acidic damage and losses caused by iron gall ink

Above: a 17th century drawing with classic signs of severe acidic damage and losses caused by iron gall ink

Iron Gall Ink is acidic, meaning it can destroy the surface it is applied upon. Some examples of this deterioration leave paper with exact holes where lettering or linear marks used to be. Whether or not the ink causes this disturbance is down to the materials used to create the paper. If you are concerned about the stability of an Iron Gall drawing or handwritten document, please get in touch with our team to discuss conservation options.

Above: iron gall drawings by Henry Fuseli (1810-16), Luca Cambiaso (1560-65) and Jacopo da Empoli (1600)

Above: iron gall drawings by Henry Fuseli (1810-16), Luca Cambiaso (1560-65) and Jacopo da Empoli (1600)

Care and display

As ink is usually applied to paper, it faces many of the usual challenges presented with this delicate material. Whilst early parchment is made of linen and cellulose without extra chemicals, they are more resilient to deterioration in colour and structure. From the 1840s onwards, paper was made from wood pulp and acidic chemicals such as lignin. This additive eventually turns the paper brown, brittle and often attracts the occurrence of foxing. Whilst this innate vulnerability cannot be avoided, you can implement care techniques to avoid any encouragement of decay. Discolouration caused by age and foxing can also be restored with excellent results following professional conservation treatments.

Above: two iron gall drawings with foxing and signs of acidic damage

Above: two iron gall drawings with foxing and signs of acidic damage

The recommended relative humidity for paper is around 50% as this ensures that it is not too moist or too dry. A very humid atmosphere, as found in bathrooms and kitchens, may result in rippling of the paper or mould growth. Conversely, a very dry atmosphere can result in a brittle surface. The ideal temperature for paper is 20 to 22 degrees celsius.

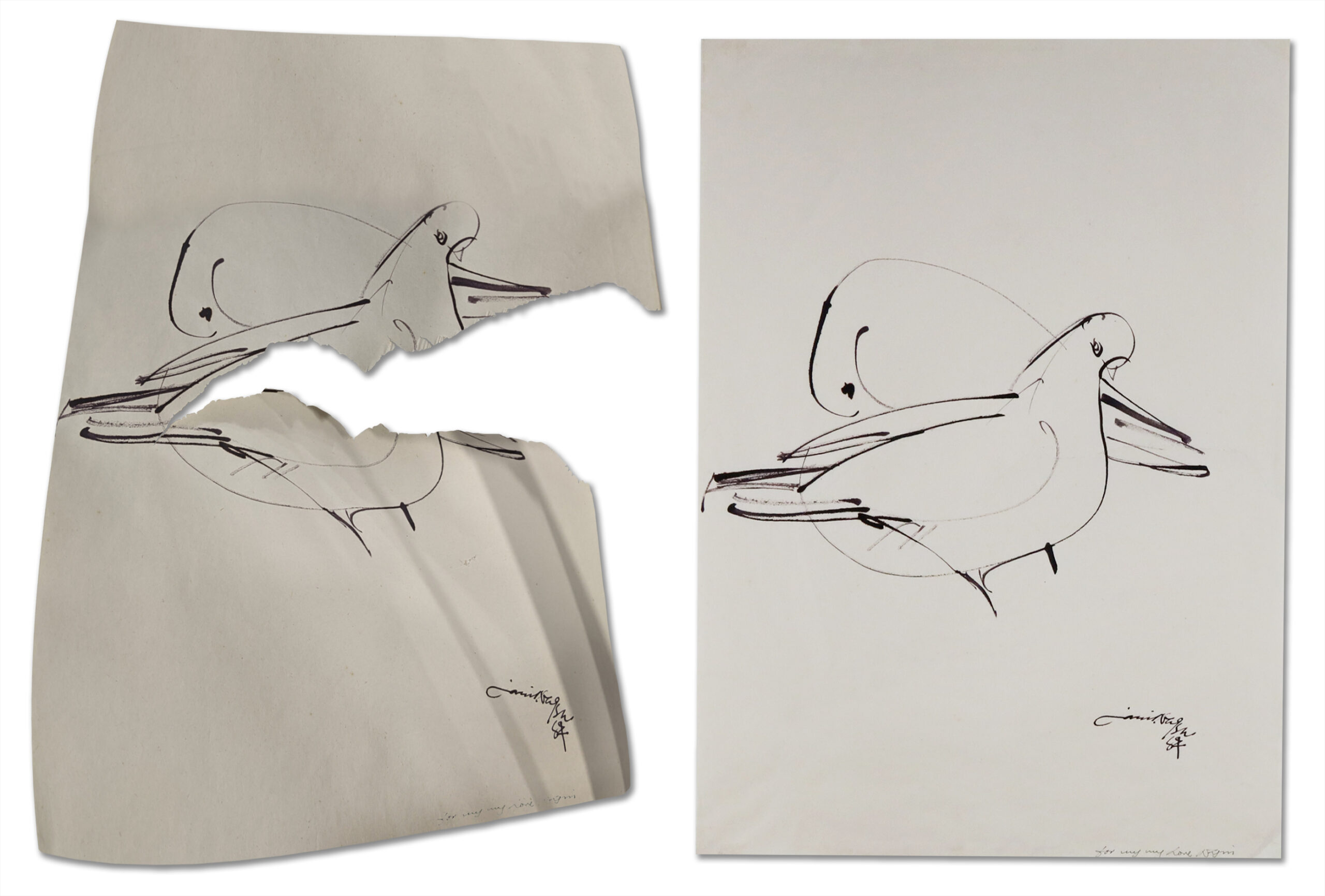

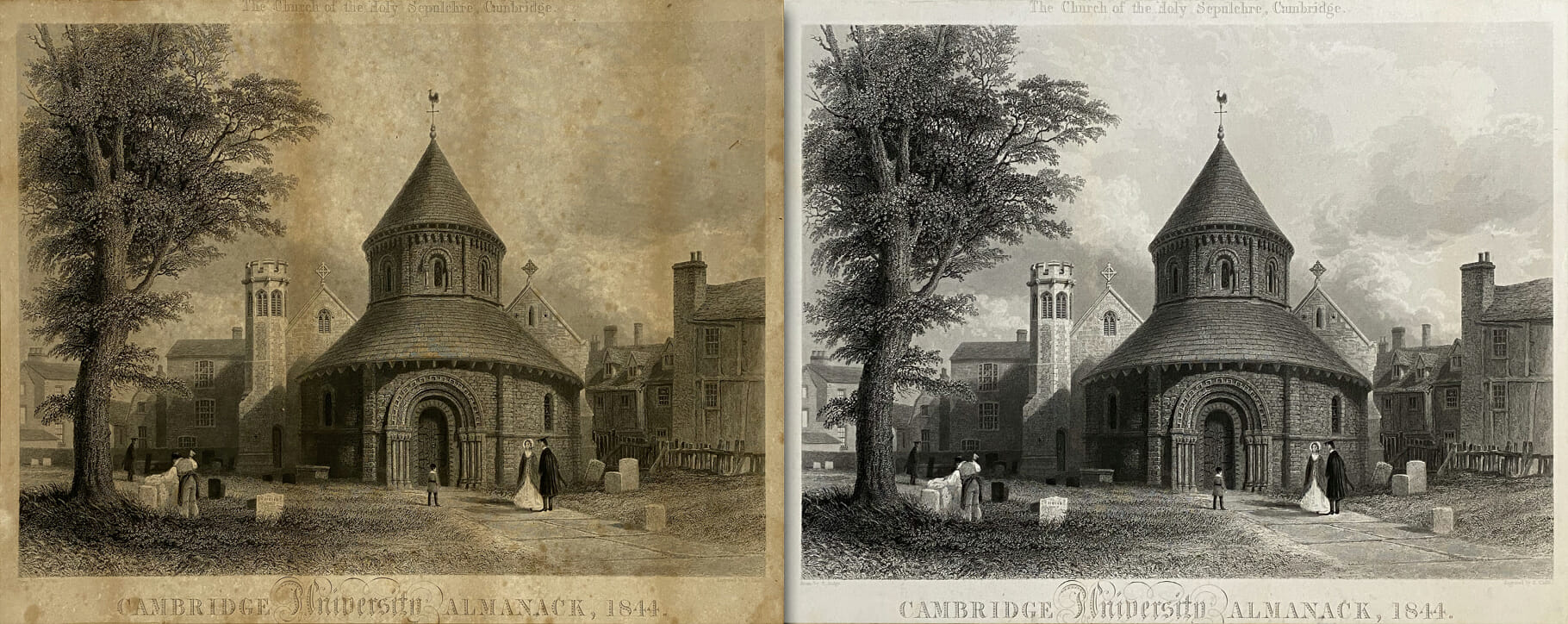

Above: two artworks with foxing and discolouration, before and after restoration by our conservator

Above: two artworks with foxing and discolouration, before and after restoration by our conservator

UV rays from sunlight and bright artificial lights may encourage some inks to fade. As this loss of colour is often widespread, it cannot be ethically restored and is usually beyond repair. To avoid loss of detail, our experts always recommend that any work on paper is displayed in shaded conditions and framed with UV protective glass or museum glass.

Above: an acid stained engraving, before and after restoration by our conservator

Above: an acid stained engraving, before and after restoration by our conservator

Framing options

As well as UV protective glazing, our team provides conservation grade frames. Acids from old framing materials discolour and harm paper. Backing boards and mounts made from inappropriate materials can lead to widespread damage. Always ensure that conservation safe materials are used in the framing process. Our framing team will always ensure that low pH materials are used.

It is recommended that old frames are assessed by our paper conservator to check for any hidden signs of acidic contaminants. Frames should be as safe and secure as possible, always check that the backing gum tape is sealing gaps to prevent an opening for dust, airborne contaminants and insects.

Our bespoke framing options also include washlines and artist name plates. Speak to a member of our team today for a personalised portfolio based on your artwork.

Ink artwork restoration

Our ICON accredited paper conservator often restores ink artworks with minor and major levels of damage. Using sensitive techniques, paper can be cleaned of acidic discolouration, foxing, water damage, and mould.

Drawings can be flattened and stabilised following occurrences of creasing, rippling and tears. Breakages caused by acidic inks, such as iron gall, cannot be reversed but they can be stabilised to prevent further deterioration by applying the paper to a non-acidic tissue.

How can we help?

If you have any questions about the restoration of ink drawings or art restoration in general, please do not hesitate to get in touch. As part of our service we offer a nationwide collection and delivery service. E-mail us via [email protected] or call 0207 112 7576 for more information.

Above: a variety of ink drawings from the renaissance to the 19th century

Above: a variety of ink drawings from the renaissance to the 19th century Above: a variety of ink drawings from the renaissance to the 19th century

Above: a variety of ink drawings from the renaissance to the 19th century Above: a pen from ancient Rome, Ming dynasty writing brush with lid, 16th century goose feather pen, 19th century silver tipped quill, and a late 18th century pen case

Above: a pen from ancient Rome, Ming dynasty writing brush with lid, 16th century goose feather pen, 19th century silver tipped quill, and a late 18th century pen case Above: detail from a pen and wash drawing of Bacchus and Ariadne by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, 1740

Above: detail from a pen and wash drawing of Bacchus and Ariadne by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, 1740 Above: a set of Qing dynasty ink cakes, 1780-94

Above: a set of Qing dynasty ink cakes, 1780-94 Above: detail from Studies of a Woman Wearing an Elaborate Headdress by an anonymous artist, retouched by Peter Paul Rubens, 1500

Above: detail from Studies of a Woman Wearing an Elaborate Headdress by an anonymous artist, retouched by Peter Paul Rubens, 1500 Above: Saint Clement by Andrea Lilio (1570-1630), Goats by Nicolaes Berchem (17th century), Battle of the Milvian Bridge by Johann Heintz (1612), Florence Leyland by James McNeill Whistler (1874) and Design for Emblematic Frontispiece “Natura Ars Emula Vincit” by Circle of Giovanni Guerra (1544-1618)

Above: Saint Clement by Andrea Lilio (1570-1630), Goats by Nicolaes Berchem (17th century), Battle of the Milvian Bridge by Johann Heintz (1612), Florence Leyland by James McNeill Whistler (1874) and Design for Emblematic Frontispiece “Natura Ars Emula Vincit” by Circle of Giovanni Guerra (1544-1618) Above: detail from The Crevasse by Rodolphe Bresdin, 1860

Above: detail from The Crevasse by Rodolphe Bresdin, 1860 Above: black ink drawings by Titian, Goya and Daumier

Above: black ink drawings by Titian, Goya and Daumier Above: study for The Departure of Jacob by François Boucher (1755), an Allegorical Figure (16th century) and an illustration for A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Arthur Rackham (1908)

Above: study for The Departure of Jacob by François Boucher (1755), an Allegorical Figure (16th century) and an illustration for A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Arthur Rackham (1908) Above: two ‘sepia’ drawings – The Actor Clairval by Étienne Aubry (18th century) and Landscape with Sheep by Claude Lorrain (1648)

Above: two ‘sepia’ drawings – The Actor Clairval by Étienne Aubry (18th century) and Landscape with Sheep by Claude Lorrain (1648) Above: a detail from a preparatory ‘sepia’ study for Perseus and the Origin of Coral by Claude Lorrain, 1671

Above: a detail from a preparatory ‘sepia’ study for Perseus and the Origin of Coral by Claude Lorrain, 1671 Above: a selection of bistre ink drawings

Above: a selection of bistre ink drawings  Above: detail from a pen and bistre drawing of Moses Trampling on Pharaoh’s Crown, 18th century

Above: detail from a pen and bistre drawing of Moses Trampling on Pharaoh’s Crown, 18th century Above: three drawings completed with pen and bistre

Above: three drawings completed with pen and bistre Above: examples of iron gall ink including a design by Jacopo della Quercia (1415-16), study of a nude by Francesco Salviati (1526-27) and a drawing by Jean-François Millet (1830-75)

Above: examples of iron gall ink including a design by Jacopo della Quercia (1415-16), study of a nude by Francesco Salviati (1526-27) and a drawing by Jean-François Millet (1830-75) Above: a 17th century drawing with classic signs of severe acidic damage and losses caused by iron gall ink

Above: a 17th century drawing with classic signs of severe acidic damage and losses caused by iron gall ink Above: iron gall drawings by Henry Fuseli (1810-16), Luca Cambiaso (1560-65) and Jacopo da Empoli (1600)

Above: iron gall drawings by Henry Fuseli (1810-16), Luca Cambiaso (1560-65) and Jacopo da Empoli (1600) Above: two iron gall drawings with foxing and signs of acidic damage

Above: two iron gall drawings with foxing and signs of acidic damage  Above: two artworks with foxing and discolouration, before and after restoration by our conservator

Above: two artworks with foxing and discolouration, before and after restoration by our conservator  Above: an acid stained engraving, before and after restoration by our conservator

Above: an acid stained engraving, before and after restoration by our conservator