Whilst ukiyo-e flourished for centuries in a commercial Japanese market, the opening of world trade at the turn of the 20th century saw new audiences for traditional prints – a westernised movement that would become known as shin-hanga.

Above: shin-hanga prints by Komori Soseki, Ito Sozan, Yoshikawa-Kenjiro Kanpô, Hiroshi Yoshida, Yamakawa Shuho, Ohara Koson and Hasui Kawase

Above: shin-hanga prints by Komori Soseki, Ito Sozan, Yoshikawa-Kenjiro Kanpô, Hiroshi Yoshida, Yamakawa Shuho, Ohara Koson and Hasui Kawase

Following the masterpieces by Hokusai and Hiroshige in the early 19th century, woodblock printers took advantage of the Western interest in Japanese culture and design. Shin-hanga artists used established themes to appeal to an enthusiastic global audience.

Above: a detail from Kingfisher in the Snow by Ohara Koson, 1925-36

Above: a detail from Kingfisher in the Snow by Ohara Koson, 1925-36

One of the most well-known of the era was Ohara Koson, a master of kacho-e (bird and flower prints). Recently, we were honoured to care for a Koson artwork in our studio with a wonderful restoration result. This article will cover the history of shin-hanga artworks, how to protect them and the sensitive restoration that can be achieved.

Above: shin-hanga prints by Kawase, Ohara Koson, Kamisaka Sekka, Hashiguchi Goyo, Kasamatsu Shiro, Tsukioka Kogyo and Yoshikawa Kanpo

Above: shin-hanga prints by Kawase, Ohara Koson, Kamisaka Sekka, Hashiguchi Goyo, Kasamatsu Shiro, Tsukioka Kogyo and Yoshikawa Kanpo

What is shin-hanga?

Shin-hanga is the term used to describe woodblock prints from the late 19th to mid 20th century – the Taisho and Showa periods. The word shin-hanga translates as 新版画 (new prints).

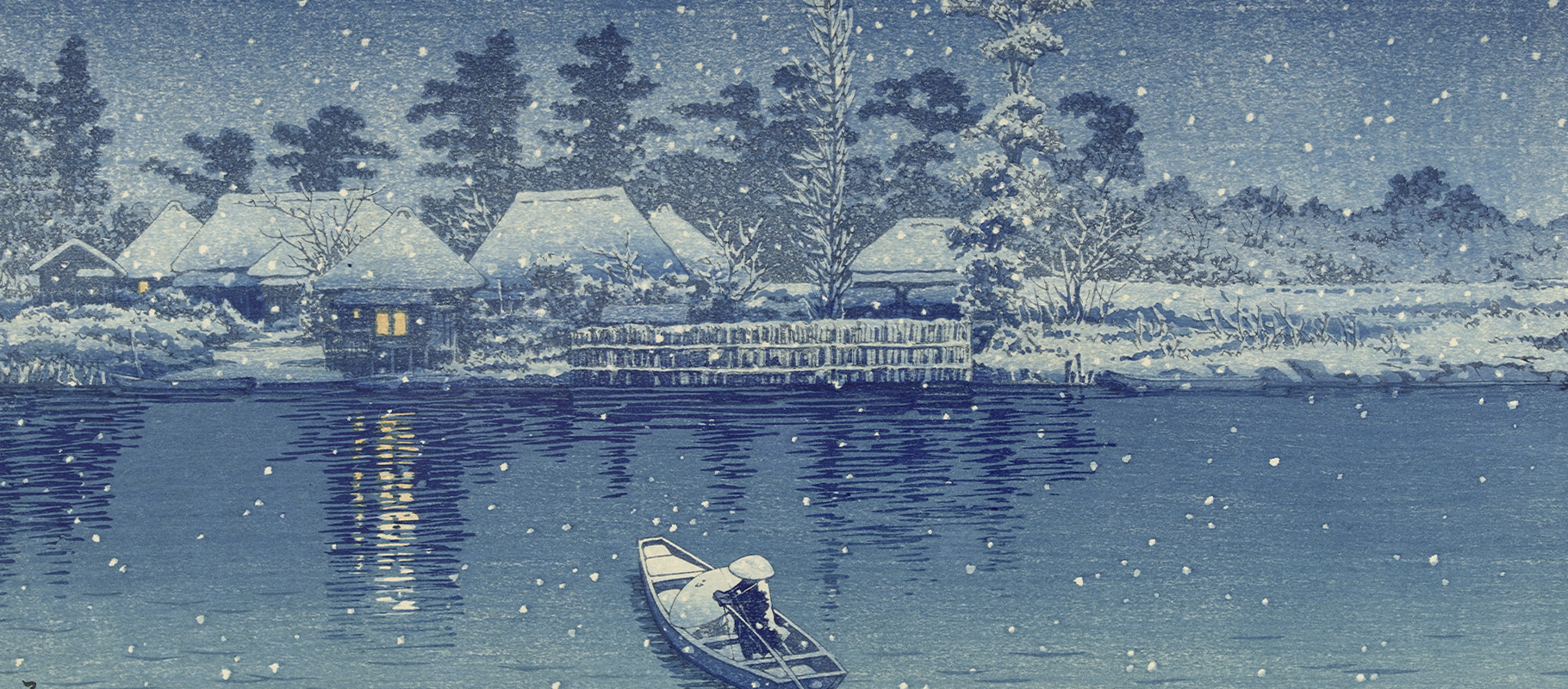

Above: detail from Ushibori by Hasui Kawase, 1930

Above: detail from Ushibori by Hasui Kawase, 1930

Modern printmaking was popular from the 1910s to 1930s – halted by the outbreak of the second world war. Due to Japan’s position in the conflict, the international market for shin-hanga waned throughout the 40s and struggled to pick up again in the 50s and 60s. However, shin-hanga has become a highly popular genre in auction houses today, Steve Jobs was a notable collector and is said to have been surrounded by walls of Hasui Kawase prints when he passed away in 2011.

Above: three yakusha-e prints depicting actors in traditional costumes, 1920s

Above: three yakusha-e prints depicting actors in traditional costumes, 1920s

Like ukiyo-e prints, shin-hanga has several traditional forms:

- Meisho (famous landmarks)

- Fukeiga (landscapes)

- Kacho-e (flowers and birds)

- Yakusha-e (actors)

- Bijinga (women)

In shin-hanga, these traditional genres were altered by European art movements such as Impressionism. ‘New prints’ are distinctive from the earlier movement (pre 1875) due to their strong gradients and dynamic use of light and shadow. This is seen clearly in the example below by Hiroshi Yoshida.

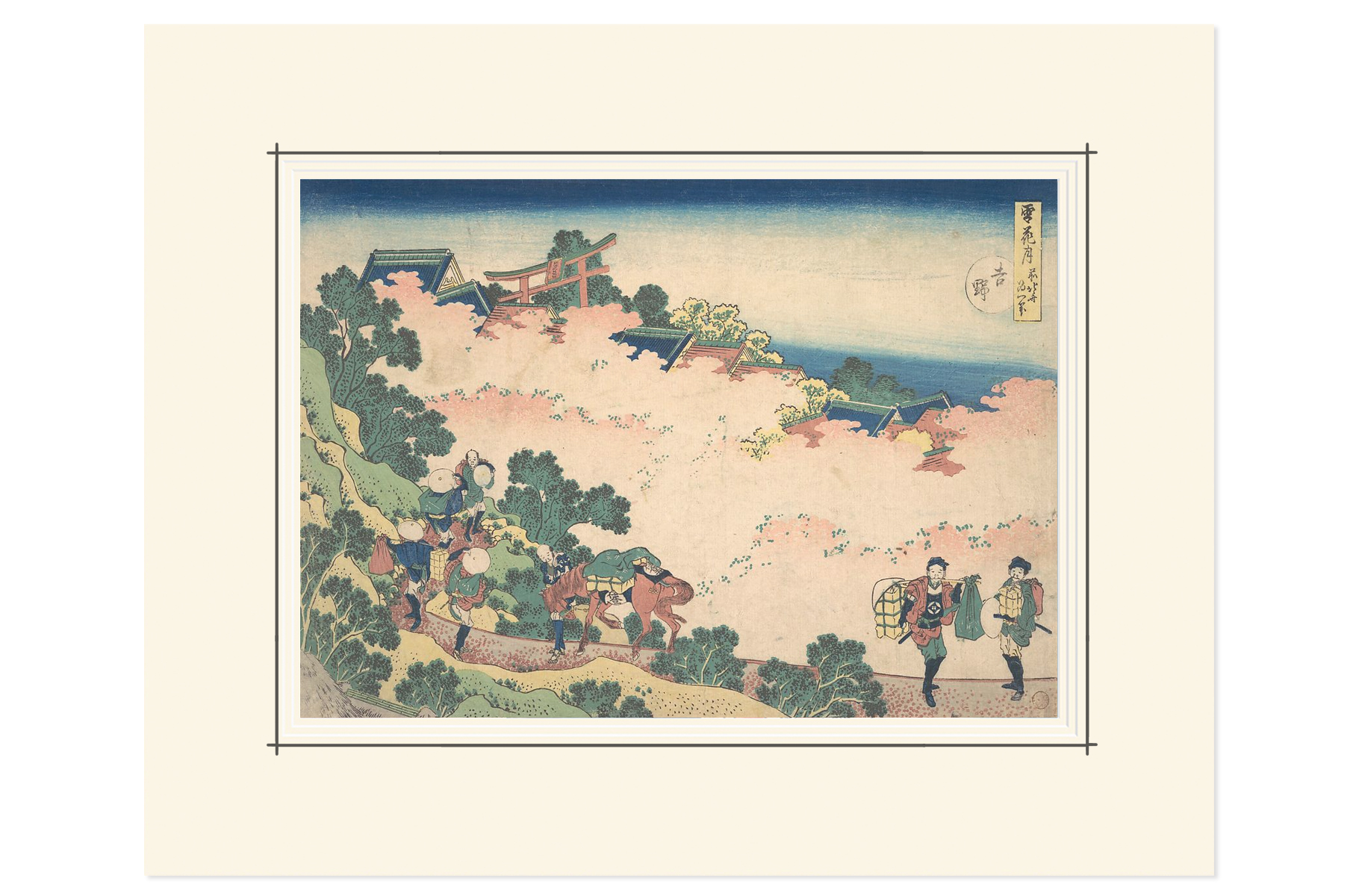

Above: a detail from a Hiroshi Yoshida print entitled Kumoi Cherry Trees, 1920

Above: a detail from a Hiroshi Yoshida print entitled Kumoi Cherry Trees, 1920

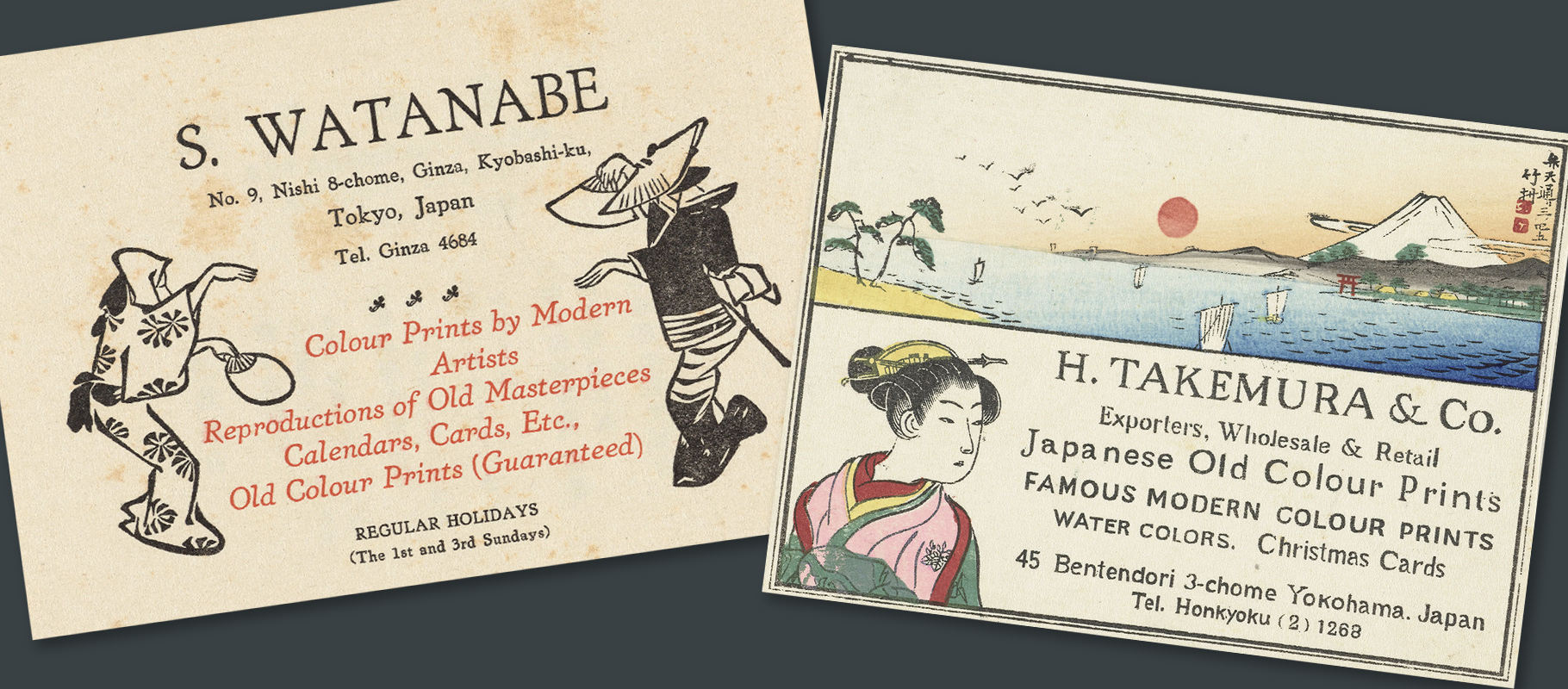

By the 1910s, Japan was becoming ever more influenced by western culture. In the Meiji era (1868-1912) art students were taught from a European tradition rather than their own. Due to this, oil paintings grew in popularity, whilst prints (now seen as out-dated) became sought after almost exclusively by the tourist market. Many shin-hanga prints were published by Watanabe Shozaburo, who coined the name of the movement in 1915.

Above: the calling cards for shin-hanga publishers aimed at the tourist market

Above: the calling cards for shin-hanga publishers aimed at the tourist market

Shin-hanga print making follows the collaborative hanmoto system. This is a division of labour between the publisher, artist, carver and printer to produce a final image rather than a singular process.

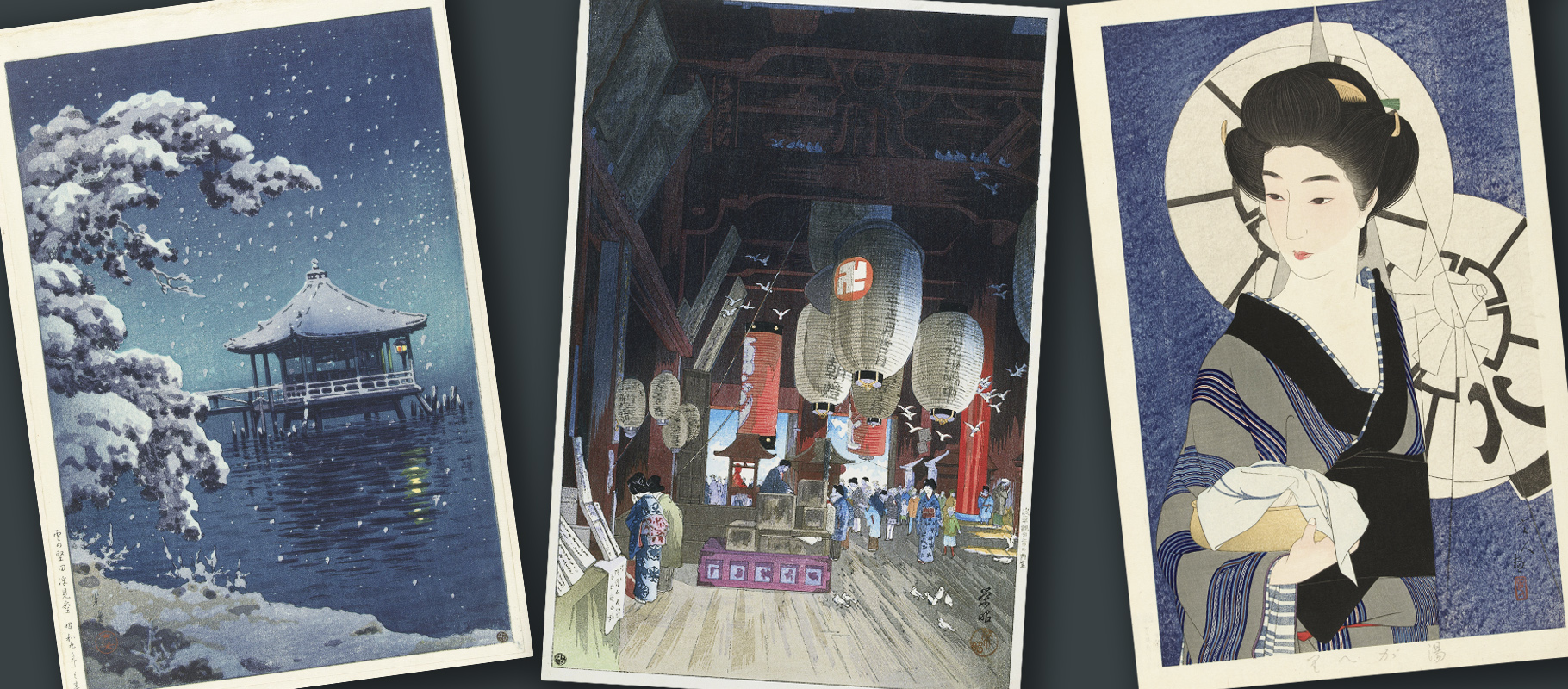

Above: Japanese prints from the 1930s by Tsuchiya Koitsu, Narazaki Eisho and Kotondo Torii

Above: Japanese prints from the 1930s by Tsuchiya Koitsu, Narazaki Eisho and Kotondo Torii

Caring for Japanese prints

Japanese prints use water or vegetable-based inks or pigments held in rice paste, making them very sensitive to moisture disturbances and extremely high risk of fading from light exposure. The paper they sit upon is also frequently handmade and may be particularly brittle due to age or environment. Ukiyo-e and Shin-hanga are some of the most vulnerable artworks on paper and require expert care to ensure longevity.

Above: a Japanese print before and after UV damage, once sunlight fades colour like this it is not reversible

Above: a Japanese print before and after UV damage, once sunlight fades colour like this it is not reversible

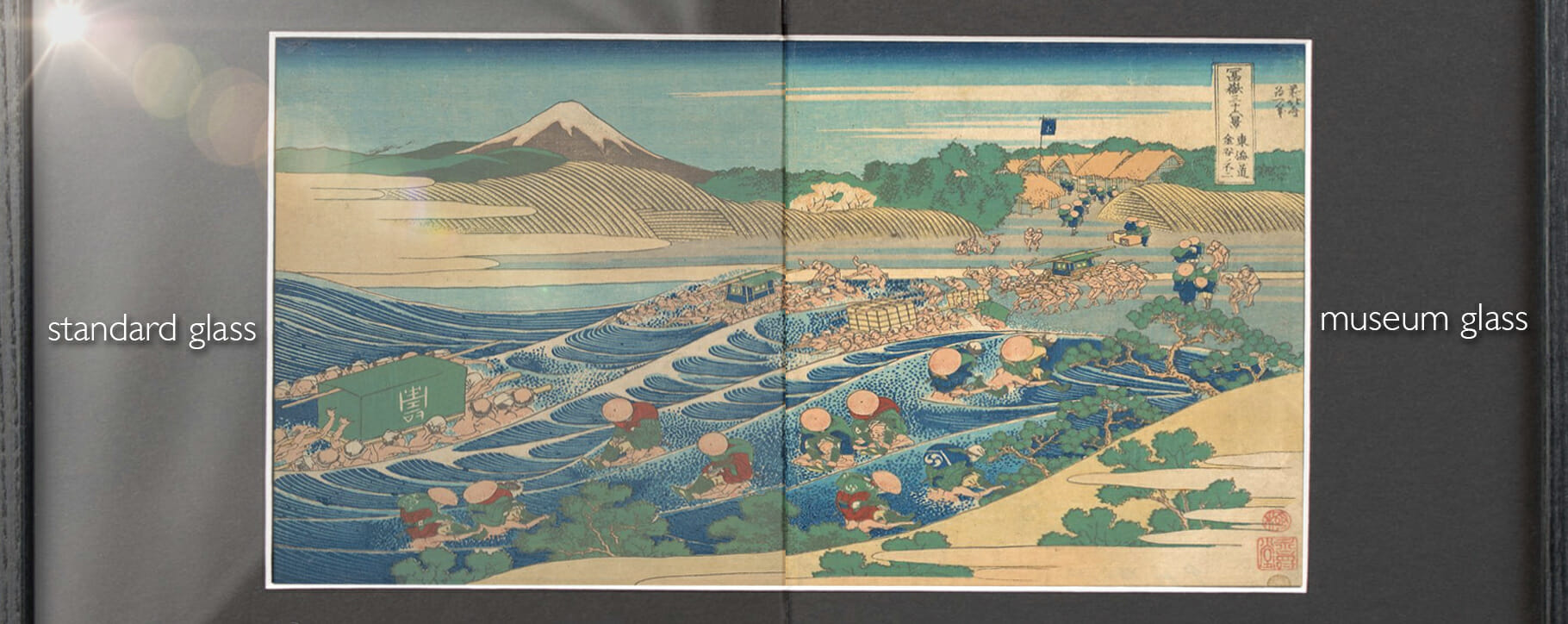

The pigments in woodblock prints can begin to fade in low levels of light, so long term display is complicated by this. When Hokusai’s ‘The Great Wave off Kanagawa’ and ‘Red Fuji’ were displayed at the British Museum, research suggested that if these prints were displayed for just three months at 50 LUX, they would have to be stored in the dark for at least a year before being exposed again. When they were displayed, it was only for 20% of the time with only a dim amount of light. For maximum protection, a storage area that is in a controlled environment and completely free of natural or artificial light is recommended.

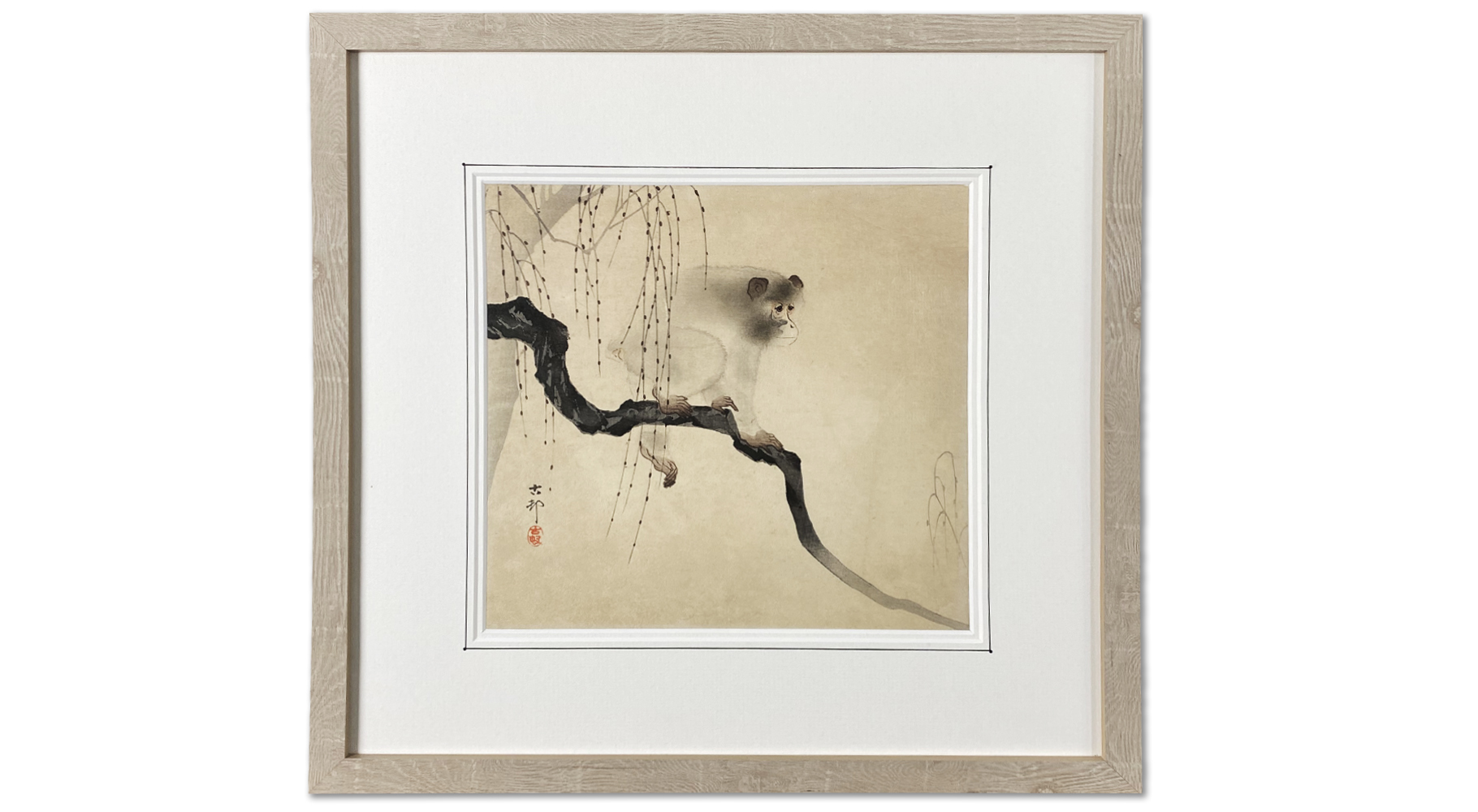

Above is an example of a mounted print, the detail is our ‘Hiroshige’ washline – this has been specifically designed to decorate Asian artworks when they are installed within protective framing. Our team is happy to offer guidance on decorative options and pH neutral mounts.

Above: an example of foxing damage on a Koson print, if left to develop this could cover the entire surface

Above: an example of foxing damage on a Koson print, if left to develop this could cover the entire surface

As the Japanese paper is usually produced in a humid environment, the humidity recommendation for Japanese woodblock prints is higher than a western work on paper. A humidity of between 50% to 60% will help to reduce risk from a dry atmosphere, but this should go no higher than 70% to avoid issues from mould and foxing.

Above: a comparison of standard glass and museum glass on a print, museum glazing is UV protective and also offers less reflection

Above: a comparison of standard glass and museum glass on a print, museum glazing is UV protective and also offers less reflection

Paper may deteriorate upon exposure to acidic framing materials. If a woodcut print is framed, it is highly recommended that UV reducing glass is in place, as well as conservation appropriate materials with a neutral PH level in the surrounding mount. Humidity can lead to the movement of paper fibres which are known to shift depending on the levels of moisture in the air. Mounts should be ensured to be flexible, as the paper can tear under drastic changes in humidity levels.

Above: a detail from a print by Kasamatsu Shiro, 1932

Above: a detail from a print by Kasamatsu Shiro, 1932

Elements of a print that were created with rice paste may face damage relating to insect infestation or mould, therefore a controlled and sterile environment is very important for their preservation. In some cases, unique three-dimensional elements make these artworks more complicated to restore and conserve. Fragile embellishments include the use of embossed lines and finely ground metallic pigments which have been set in glue. Appropriate framing or storage mounts are required to prevent any rubbing, disruption or deterioration of these areas.

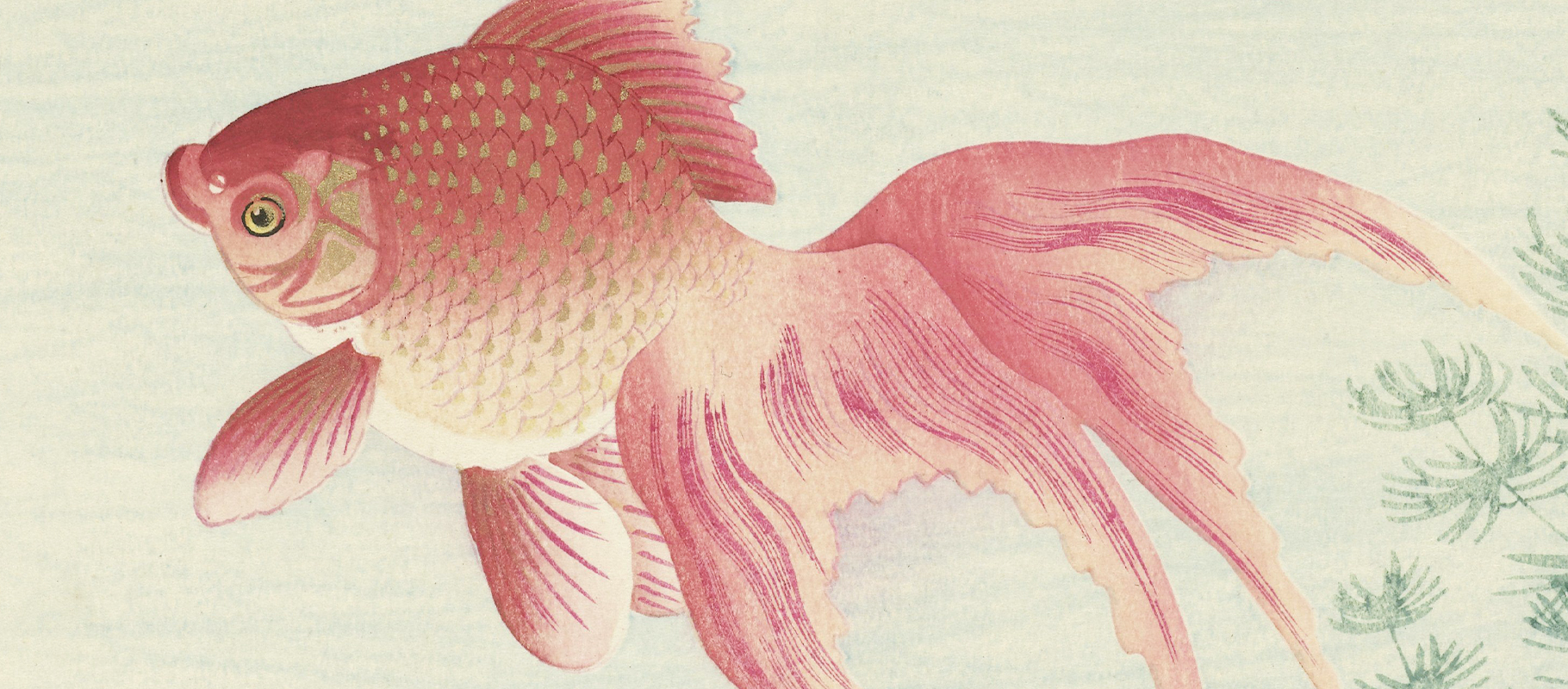

Above: a print by Ohara Koson with a layer of gold detailing

Above: a print by Ohara Koson with a layer of gold detailing

Ohara Koson restoration

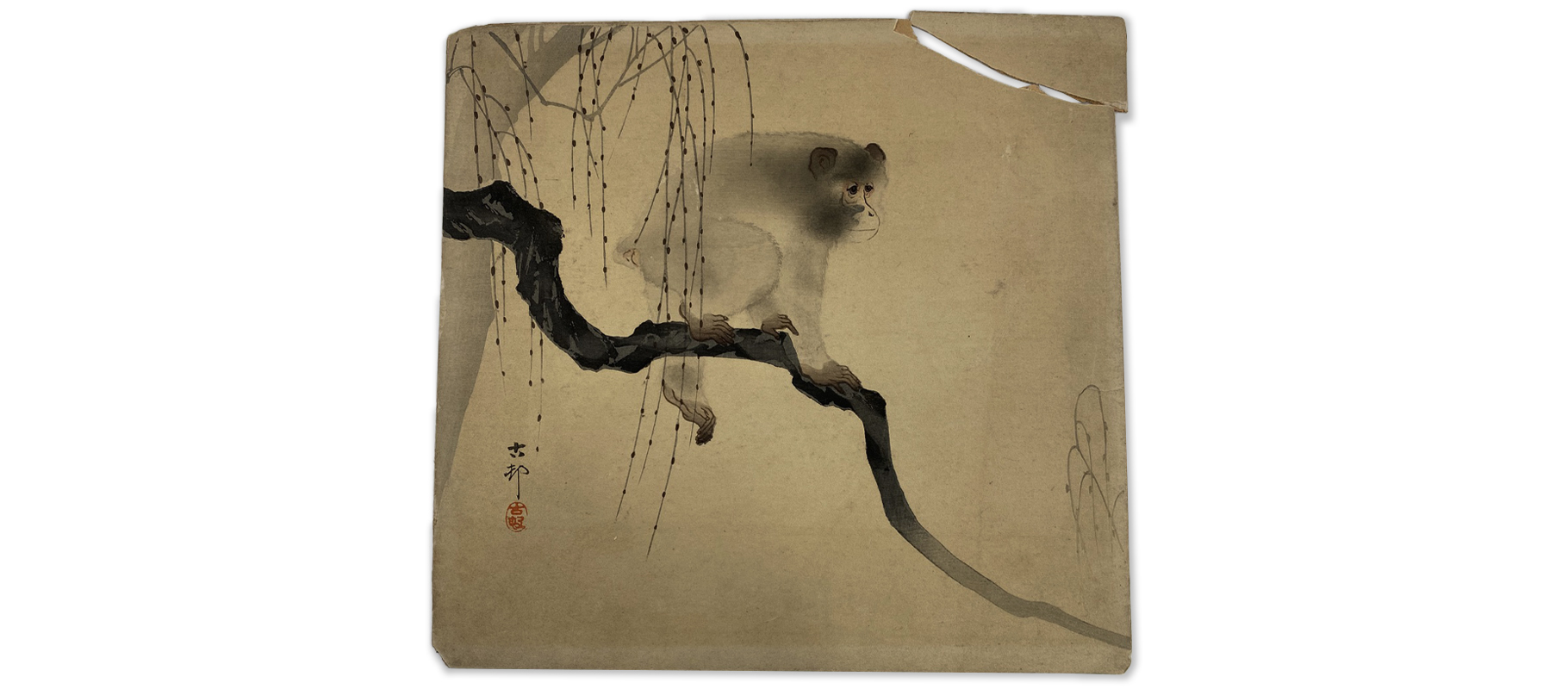

Our team recently restored a print by Ohara Koson following discolouration and tear damage. Koson was one of the most prolific shin-hanga artists, creating over 500 prints during his career.

Above: a selection of kacho-e prints by Ohara Koson, 1900-1930s

Above: a selection of kacho-e prints by Ohara Koson, 1900-1930s

Many of these were published by the influential Watanabe Shozaburo, as well as Kawaguchi, Kokkeido and Daikokuya. Koson’s prints can now be found in famous art collections around the world, including the British Museum and Rijksmuseum. As a master of the kacho-e genre, his prints usually include flowers, birds and mammals. The example that came to our studio was an early 20th century print entitled Monkey on a Branch.

The darkening surface would have been encouraged by prior storage or display conditions, as well as atmospheric contaminants. This may also be due to the materials within the paper, as we often find that post-industrial pulp is more likely to brown with age. Our paper conservator tested the surface before gently washing the print in a customised solution. This lifts the discolouration whilst retaining the original pigments of the piece. After the cleaning process, tear damage was addressed by carefully knitting the fibres back together. The print was mounted onto a pH neutral Japanese tissue paper for added stability.

When selecting a new, protective frame our client selected a simple wooden moulding with a mount line entitled ‘Hokusai’ to add a complimentary feature. The line was hand-drawn by our frame conservator, who also mounted the print with conservation-appropriate materials. The finished result allowed the Koson artwork to return to display in a safe and stable condition.

How can we help?

If you have a Japanese print or artwork in need of professional care, please speak to our helpful team today. Email us via [email protected] or call 0207 112 7576

Above: shin-hanga prints by Komori Soseki, Ito Sozan, Yoshikawa-Kenjiro Kanpô, Hiroshi Yoshida, Yamakawa Shuho, Ohara Koson and Hasui Kawase

Above: shin-hanga prints by Komori Soseki, Ito Sozan, Yoshikawa-Kenjiro Kanpô, Hiroshi Yoshida, Yamakawa Shuho, Ohara Koson and Hasui Kawase Above: a detail from Kingfisher in the Snow by Ohara Koson, 1925-36

Above: a detail from Kingfisher in the Snow by Ohara Koson, 1925-36 Above: shin-hanga prints by Kawase, Ohara Koson, Kamisaka Sekka, Hashiguchi Goyo, Kasamatsu Shiro, Tsukioka Kogyo and Yoshikawa Kanpo

Above: shin-hanga prints by Kawase, Ohara Koson, Kamisaka Sekka, Hashiguchi Goyo, Kasamatsu Shiro, Tsukioka Kogyo and Yoshikawa Kanpo Above: detail from Ushibori by Hasui Kawase, 1930

Above: detail from Ushibori by Hasui Kawase, 1930 Above: three yakusha-e prints depicting actors in traditional costumes, 1920s

Above: three yakusha-e prints depicting actors in traditional costumes, 1920s Above: a detail from a Hiroshi Yoshida print entitled Kumoi Cherry Trees, 1920

Above: a detail from a Hiroshi Yoshida print entitled Kumoi Cherry Trees, 1920 Above: the calling cards for shin-hanga publishers aimed at the tourist market

Above: the calling cards for shin-hanga publishers aimed at the tourist market Above: Japanese prints from the 1930s by Tsuchiya Koitsu, Narazaki Eisho and Kotondo Torii

Above: Japanese prints from the 1930s by Tsuchiya Koitsu, Narazaki Eisho and Kotondo Torii  Above: a Japanese print before and after UV damage, once sunlight fades colour like this it is not reversible

Above: a Japanese print before and after UV damage, once sunlight fades colour like this it is not reversible Above: an example of foxing damage on a Koson print, if left to develop this could cover the entire surface

Above: an example of foxing damage on a Koson print, if left to develop this could cover the entire surface Above: a comparison of standard glass and museum glass on a print, museum glazing is UV protective and also offers less reflection

Above: a comparison of standard glass and museum glass on a print, museum glazing is UV protective and also offers less reflection  Above: a detail from a print by Kasamatsu Shiro, 1932

Above: a detail from a print by Kasamatsu Shiro, 1932 Above: a print by Ohara Koson with a layer of gold detailing

Above: a print by Ohara Koson with a layer of gold detailing  Above: a selection of kacho-e prints by Ohara Koson, 1900-1930s

Above: a selection of kacho-e prints by Ohara Koson, 1900-1930s