The story of Wedgwood is not only one of great creative influence, but industrial ingenuity. In an era when the potteries of Great Britain had a rather unsophisticated production line, Josiah Wedgwood stepped forth to revolutionise and popularise an efficient yet highly artistic output of marketable earthenware and stoneware.

Above: various items by Wedgwood including a candlestick, tray, cup and cameo portraits

Above: various items by Wedgwood including a candlestick, tray, cup and cameo portraits

This article will detail the history of Wedgwood and their innovative Jasperware and Black Basalt ceramics. We will also explore the conservation and restoration of these beautiful antiques, including the results that can be achieved by our specialist conservators. If you are hoping to age your item, click here to find out more about Wedgwood Maker’s Marks.

Above: a collection of Wedgwood relief plaques, 18th century

Above: a collection of Wedgwood relief plaques, 18th century

Who was Josiah Wedgwood?

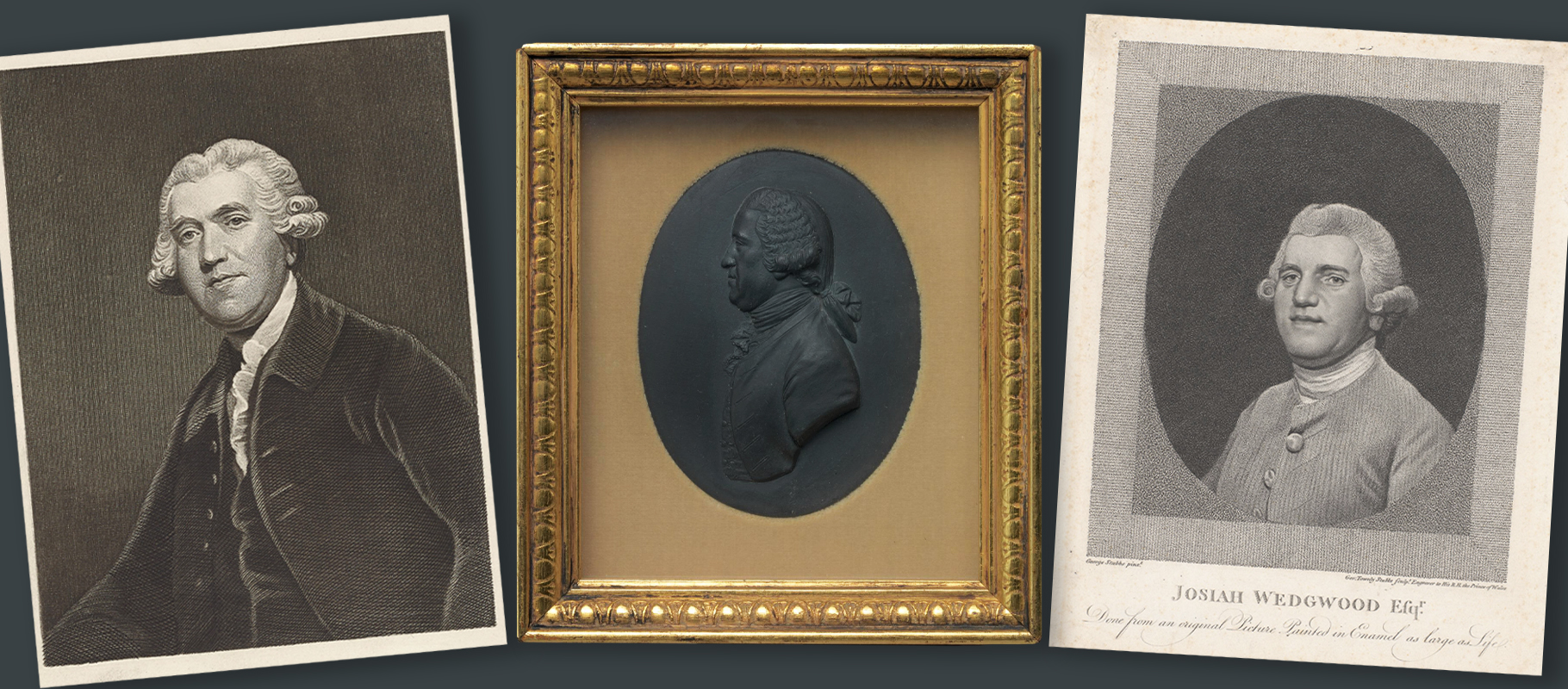

Like many families in Staffordshire, Wedgwood came from a long line of potters working in the thriving local industry. Born in the town of Burslem in 1730, Josiah was the youngest of eleven children. He suffered from smallpox in his youth, resulting in a damaged knee that would plague him for the rest of his life, eventually causing the loss of his leg. This disability prevented Wedgwood from taking up the potter’s wheel, leading him to draw the designs instead.

Above: three portraits of Josiah Wedgwood, including an engraving after a painting by Joshua Reynolds, a Wedgwood Black Basalt relief by John Flaxman and an engraving after an enamel cameo

Above: three portraits of Josiah Wedgwood, including an engraving after a painting by Joshua Reynolds, a Wedgwood Black Basalt relief by John Flaxman and an engraving after an enamel cameo

Although he had no formal education, Josiah Wedgwood’s apprenticeships under his father, brother and experienced potters of the era allowed him to develop a deep understanding of the industry and its processes. He also had enthusiasm for scientific developments, eventually leading him to cultivate both interests into an innovative pottery business.

Above: a selection of pottery from the studio of Wedgwood’s business partner Thomas Whieldon, mid 18th century

Above: a selection of pottery from the studio of Wedgwood’s business partner Thomas Whieldon, mid 18th century

After completing work with Thomas Whieldon, Wedgwood had a clear view of what he called the ‘elegance of form’. He hoped to improve upon the glazes and body of the clay, as well as the overall style and colour of decorative items and homeware. Realising the potential for new ceramic forms, Wedgwood said “I saw the field was spacious, and the soil so good as to promise an ample recompense to anyone who should labour diligently.”

Above: cameo portrait of Wilhelmina van Pruisen (1782), the Wedgwood interpretation of the Borghese Vase (1780-1800), and a white jasperware plate (1790)

Above: cameo portrait of Wilhelmina van Pruisen (1782), the Wedgwood interpretation of the Borghese Vase (1780-1800), and a white jasperware plate (1790)

His experiments would yield admirable results, leading to such an expansion of his business that by 1768 he had constructed the largest pottery manufactory in the world. The new premises were called Etruria, after an archaeological site in Italy that had unearthed many pots and ceramic artefacts from ancient Rome. This neoclassical fascination was inspired by a new business partner called Thomas Bentley, who introduced Josiah to many of the classical collectors of the era including the British Consul to Naples, William Hamilton.

Above: a neoclassical Wedgwood plaque after a design by Lady Templetown, 1785-90

Above: a neoclassical Wedgwood plaque after a design by Lady Templetown, 1785-90

Wedgwood was a lifelong Unitarian and had strong support for the abolition of slavery, writing to Benjamin Franklin in 1788 and producing cameo medallions to support the cause. His conscientious view on social issues also led him to provide homes for his workers. Wedgwood’s workforce was primarily made up of skilled local people, he had a keen interest in education and at the end of his career almost a quarter of his staff were apprentices – taking on both boys and girls. To maintain the highest standards, his factory was revolutionary in terms of its orderliness and cleanliness.

Above: three anti-slavery items from the Wedgwood workshop

Above: three anti-slavery items from the Wedgwood workshop

Following his death, a Wedgwood Memorial Institute was set up in his hometown. The ceremonial foundation was laid by William Gladstone, who said “He was the greatest man who ever, in any age or any country, applied himself to the important work in uniting art with industry.” His legacy was continued by his children, many later pieces from the Wedgwood factory have the name of his sons. Through his family, Josiah also has an important connection to modern science; in 1809 his daughter Susannah gave birth to Charles Darwin.

Above: a collection of relief horses by George Stubbs (1820) and a covered vase (1850)

Above: a collection of relief horses by George Stubbs (1820) and a covered vase (1850)

Classical influences

In the late 18th century there was a revival of classical forms in all aspects of art and design. This was in part influenced by the printing press, which had allowed the upper classes to gain access to newly translated editions of ancient mythology and philosophy. The enlightenment period celebrated these works as being one of the highest forms of thinking and the starting point of western civilisation. The ever growing imperialism of British aristocracy saw themselves reflected in the stories of ancient Rome, as a continuation of this romanticised era.

Above: a selection of neoclassical Wedgwood designs

Above: a selection of neoclassical Wedgwood designs

When Wedgwood met Thomas Bentley, his eyes were opened to the growing influence of classical ideas. The neoclassical movement was encouraged further following the discovery of numerous artefacts, including copious amounts of ancient pottery. Just as the aristocrats saw themselves as the heirs of romanticised ancient power, Wedgwood would have placed himself in a direct line of famous pottery masters, going as far back as Hellenistic Greece. Keen to create fashionable and timeless pieces, he researched the forms being unearthed by archeologists and quickly implemented them in his studio. When his new factory opened in 1769, Wedgwood had the first vases imprinted with ‘The Arts of Etruria are reborn’.

Above: a glazed creamware ewer, a balsalt bust of Democritus, a porphyry style vase, and a basalt ewer designed by John Flaxman

Above: a glazed creamware ewer, a balsalt bust of Democritus, a porphyry style vase, and a basalt ewer designed by John Flaxman

Many of Wedgwood’s most famous ceramics are directly copied from classical pottery, interpreted into forms of Jasperware and Black Basalt. The most celebrated example is Wedgwood’s Portland Vase – interpreted from the Barberini Vase discovered in Rome. The Barberini Vase was found in a sarcophagus under a burial mound and was purchased by collector William Hamilton, who later sold it in England to the Duchess of Portland. After her death in 1785, Wedgwood arranged to have it on loan to copy. This was a painstaking task, as Wedgwood wanted to create a perfect replica of what was a ‘perfect’ piece of classical art. The finished copies would later prove to be vital, as the original Barberini Vase was smashed into hundreds of pieces when it was put on display in The British Museum. Using Wedgwood’s copy, the conservators were able to accurately repair the vase and return it to display.

Above: the Wedgwood Portland Vase viewed from two angles

Above: the Wedgwood Portland Vase viewed from two angles

Jasperware

The most famous material in the Wedgwood catalogue is Jasperware, an unglazed vitreous stoneware. It was not an easy task, taking Wedgwood over 10,000 attempts to achieve the correct process. The finished result allowed stoneware to be fired in fashionable pastel shades of blue, pink, yellow, green and lilac, as well as grey, white, maroon and black. This long and intricate experiment led Josiah Wedgwood to be the first potter to invent a pyrometer to accurately record the kiln temperatures.

Above: a selection of jasperware pieces including a cup, a fork, portrait medallion, cabinet, bowl and flask

Above: a selection of jasperware pieces including a cup, a fork, portrait medallion, cabinet, bowl and flask

Although it is named after jasper, the ceramic body is likely made up of around 29% ball clay, 57% barium sulphate, 10% flint and 4% barium carbonate. However, the actual arcanum for Jasperware is a closely guarded secret. This combination is then mixed with different additives to create colour, such as cobalt and manganese oxide. Due to a high firing temperature, the overall body of Jasperware is strong due to its minimal pores.

Above: a selection of Jasperware colours used in the Wedgwood factory

Above: a selection of Jasperware colours used in the Wedgwood factory

Many of the decorative features on Wedgwood’ Jasperware were designed by skilled artists, including George Stubbs, John Flaxman, Lady Templeton and William Hackwood. The interior designer Robert Adam was a great fan of Jasperware, placing pastel Wedgwood pieces in his neoclassical rooms up and down the country.

Above: a selection of jasperware items including a covered vase, relief panel, teacup set, plinth and chess pieces

Above: a selection of jasperware items including a covered vase, relief panel, teacup set, plinth and chess pieces

Creamware

To compete with the market for porcelain dining sets and other household ceramics, Wedgwood perfected his creamware range to provide a more durable alternative. Whilst much creamware was left undecorated – allowing the shape to be admired alone – a selection of pieces did undergo transfer printing. Others had their blank sides personalised, often with witty lines and poetry, as well as commemorative dates. As Wedgwood’s earliest successes were in the sale of creamware to Queen Charlotte, these pieces are sometimes referred to as Queensware.

Above: a selection of Wedgwood creamware

Above: a selection of Wedgwood creamware

Black Basalt

Composed by staining unglazed stoneware with manganese dioxide and cobalt, Black Basalt quickly became a staple in Wedgwood designs following its creation in 1768. Inspired by ‘Egyptian Black’ pottery, the dark stoneware contrasted with the white or cream porcelain that traditionally dominated the ceramics market.

Above: a selection of black basalt wares by Wedgwood including a plate, teacup, relief cameo, intaglio seals, teapots and a covered vase

Above: a selection of black basalt wares by Wedgwood including a plate, teacup, relief cameo, intaglio seals, teapots and a covered vase

Black Basalt was often decorated with white neoclassical reliefs, as well as red enamels to replicate ancient Greek designs. Cameo portraits, busts and intaglio pieces for sealing wax were also popular. In the early 19th century, Black Basalt was also decorated with a famille rose style ‘Chrysanthemum pattern’ inspired by Chinese designs.

Above: three black basalt items including a bust of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, a Chrysanthemum pattern vase and a Jardiniere

Above: three black basalt items including a bust of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, a Chrysanthemum pattern vase and a Jardiniere

Wedgwood restoration

Our ceramics conservator is experienced in a great variety of mediums, including the unique finishes found on Wedgwood items. A recent project in our studio was the restoration of two large covered vases, recognisable as Wedgwood’s Pegasus Vase designed by John Flaxman.

The Pegasus Vase features decoration taken from a Greek design dated to the 4th century BC, the original was presented to the British Museum in 1763 from the Hamilton collection. Known as the ‘Apotheosis of Homer’ the figurative story of the vase shows the ancient poet Homer being crowned as a god for his creative genius. An apotheosis scene was usually reserved for kings and rulers after their death, but cults surrounded the likes of Homer and other writers – much like the modern idea of celebrity. Flaxman’s choice of scene reflects how Wedgwood saw themselves as a manufacturer in the late 18th century, as a British continuation of glorified ancient artists.

Above: a close-up of the vase prior to conservation treatments

Above: a close-up of the vase prior to conservation treatments

The biscuit texture of unglazed ceramics is an attractive resting ground for historic contaminants such as dust, fireplace soot, nicotine and other atmospheric particles. Unlike glazed porcelain, contaminants may stick more readily to a matt surface and can build up over time. This was the case with areas of the vases our conservator cared for, as much of the original white detailing had yellowed. The entire surface of both vases were cleaned with a small cotton swab, using a solution that was tested against the materials for a safe and effective removal of the discolouration.

Any areas of physical damage are then assessed for their stability, such as cracking, historic glue and loosening of applied decoration. These can be consolidated sensitively, allowing the vase to still show its age whilst ensuring it is safe for future generations. Our conservators can also recreate and repair missing areas by creating the same Wedgwood style colour and patina to match in with the original surface as seamlessly as possible.

Above: the stand and lid of the Pegasus vase before and after restoration

Above: the stand and lid of the Pegasus vase before and after restoration

How can we help?

Our conservation team is happy to offer advice and assist you with any restoration concerns. E-mail us via [email protected] or call 0207 112 7576 for more information.

Above: various items by Wedgwood including a candlestick, tray, cup and cameo portraits

Above: various items by Wedgwood including a candlestick, tray, cup and cameo portraits Above: a collection of Wedgwood relief plaques, 18th century

Above: a collection of Wedgwood relief plaques, 18th century  Above: three portraits of Josiah Wedgwood, including an engraving after a painting by Joshua Reynolds, a Wedgwood Black Basalt relief by John Flaxman and an engraving after an enamel cameo

Above: three portraits of Josiah Wedgwood, including an engraving after a painting by Joshua Reynolds, a Wedgwood Black Basalt relief by John Flaxman and an engraving after an enamel cameo Above: a selection of pottery from the studio of Wedgwood’s business partner Thomas Whieldon, mid 18th century

Above: a selection of pottery from the studio of Wedgwood’s business partner Thomas Whieldon, mid 18th century Above: cameo portrait of Wilhelmina van Pruisen (1782), the Wedgwood interpretation of the Borghese Vase (1780-1800), and a white jasperware plate (1790)

Above: cameo portrait of Wilhelmina van Pruisen (1782), the Wedgwood interpretation of the Borghese Vase (1780-1800), and a white jasperware plate (1790)

Above: three anti-slavery items from the Wedgwood workshop

Above: three anti-slavery items from the Wedgwood workshop Above: a collection of relief horses by George Stubbs (1820) and a covered vase (1850)

Above: a collection of relief horses by George Stubbs (1820) and a covered vase (1850) Above: a selection of neoclassical Wedgwood designs

Above: a selection of neoclassical Wedgwood designs Above: a glazed creamware ewer, a balsalt bust of Democritus, a porphyry style vase, and a basalt ewer designed by John Flaxman

Above: a glazed creamware ewer, a balsalt bust of Democritus, a porphyry style vase, and a basalt ewer designed by John Flaxman  Above: the Wedgwood Portland Vase viewed from two angles

Above: the Wedgwood Portland Vase viewed from two angles  Above: a selection of jasperware pieces including a cup, a fork, portrait medallion, cabinet, bowl and flask

Above: a selection of jasperware pieces including a cup, a fork, portrait medallion, cabinet, bowl and flask Above: a selection of Jasperware colours used in the Wedgwood factory

Above: a selection of Jasperware colours used in the Wedgwood factory Above: a selection of jasperware items including a covered vase, relief panel, teacup set, plinth and chess pieces

Above: a selection of jasperware items including a covered vase, relief panel, teacup set, plinth and chess pieces  Above: a selection of Wedgwood creamware

Above: a selection of Wedgwood creamware Above: a selection of black basalt wares by Wedgwood including a plate, teacup, relief cameo,

Above: a selection of black basalt wares by Wedgwood including a plate, teacup, relief cameo,  Above: three black basalt items including a bust of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, a Chrysanthemum pattern vase and a Jardiniere

Above: three black basalt items including a bust of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, a Chrysanthemum pattern vase and a Jardiniere Above: a close-up of the vase prior to conservation treatments

Above: a close-up of the vase prior to conservation treatments  Above: the stand and lid of the Pegasus vase before and after restoration

Above: the stand and lid of the Pegasus vase before and after restoration