The respect and worship of ancestral heritage has been practiced in China for many centuries, resulting in the creation of portraiture of artistic and familial significance. Dating as far back as the Ming dynasty, these paintings on silk, paper and canvas are so detailed that they can provide historians with vital evidence of lineage, rank and visual styles.

Above: detail from a portrait scroll depicting several generations of one family

Above: detail from a portrait scroll depicting several generations of one family

Chinese portraits are innately sensitive due to the materials used in their composition, as well as carrying strong cultural importance for families around the world. This implication means that they benefit from an expert conservation approach for restoration and display. This article will look at the history of these beautiful portraits, as well as how they can be restored in our studio and safely mounted in bespoke, protective frames.

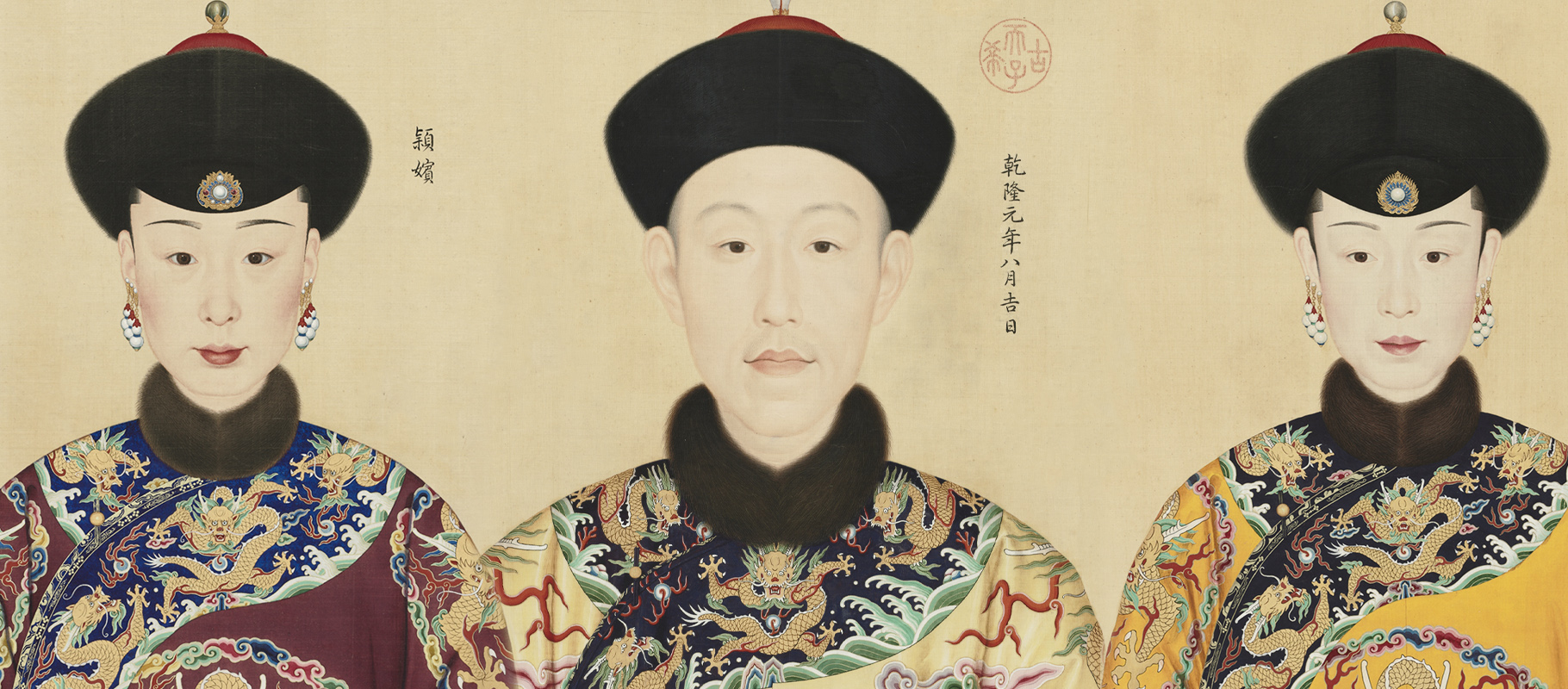

Above: imperial portraits of a lady, the Yongzheng Emperor, a Yongzheng Empress and a Qianlong Empress, all from the 19th Century

Above: imperial portraits of a lady, the Yongzheng Emperor, a Yongzheng Empress and a Qianlong Empress, all from the 19th Century

Ancestral portraiture in China

Paper has been traditionally crafted in China as far back as the Han period, many decades before the medium arrived in Europe. It became a vital feature of interior design and communication, often combining both to create a visually magnificent scroll, screen or wall panel to exemplify a family’s reputation. You can read more about Chinese panel art here.

Above: detail from a large group portrait, 1796-1820

Above: detail from a large group portrait, 1796-1820

In imperial China, rank was a vital part of daily life, strictly dictating all social customs. In many cases, an entire extended family could be raised or lowered in class based on a relative’s luck or misfortune. Obtaining a high rank through a position in the military, civil service or imperial house was to be celebrated not only as an individual achievement, but for the entire family and generations to come.

Above: two pages from a family portrait album, mid 19th century

Above: two pages from a family portrait album, mid 19th century

Rank is displayed so clearly through clothing and symbolic features that further context is usually not required by the viewer. Fine brushwork details the most intricate areas of a luxurious robe, hat or accessory. However, this could be altered by later generations – if a son or grandson achieved a higher rank, they could apply the same visual indicators to their ancestors.

Above: details from a portrait of the Qianlong Emperor as a young man, 19th century

Above: details from a portrait of the Qianlong Emperor as a young man, 19th century

In all cultures, portraiture plays an important role in displaying social standing, immortalising personal fortune and status. This visual connection to the past allows for a tangible reminder of our lineage, one that was of significant consequence to Chinese families living under imperial rule.

In China, portraiture became a way to not only respect past family members, but worship them. This reverence was an important part of cultural holidays, when families would place food in front of an artwork in appreciation. If this custom was ignored, it was feared that their ancestral ghosts would wreak havoc upon the living family.

Above: an embellished portrait that would have been commissioned during the life of the sitter and re-purposed after his death for veneration in an ancestral shrine, late 18th / early 19th century

Above: an embellished portrait that would have been commissioned during the life of the sitter and re-purposed after his death for veneration in an ancestral shrine, late 18th / early 19th century

Traditional ancestral portraits became popular in the Ming and particularly Qing dynasties, commissioned to commemorate the dead. In many cases, they were completed as a pair – allowing a husband and wife to sit alongside each other. This is another important feature that compels rank and status, allowing married couples to benefit in life and death from a prosperous arrangement.

Above: portrait of an old lady (1561-1621), portrait of a husband and wife (late 18th-early 19th century), portrait of the artist’s Great Grand Uncle Yizhai at the age of Eighty-Five (1561-1621)

Above: portrait of an old lady (1561-1621), portrait of a husband and wife (late 18th-early 19th century), portrait of the artist’s Great Grand Uncle Yizhai at the age of Eighty-Five (1561-1621)

Ancestral portraits were composed by a workshop of artists, working together on different elements. As there were so many portraits of this kind being commissioned, set formats for body shape and clothing were established – changing only the face of the sitter to achieve a realistic finish.

Above: a portrait of the Qianlong Emperor (centre) and two of his consorts, 1736–70

Above: a portrait of the Qianlong Emperor (centre) and two of his consorts, 1736–70

Typically no images were available of the deceased, so family members could pick features such as the correct eyes, nose and mouth from a range of pre-made choices. This would then be composed together using brushes of various sizes, taking into account the appearance of living family members to make the portrait as accurate as possible.

Caring for Chinese portraits

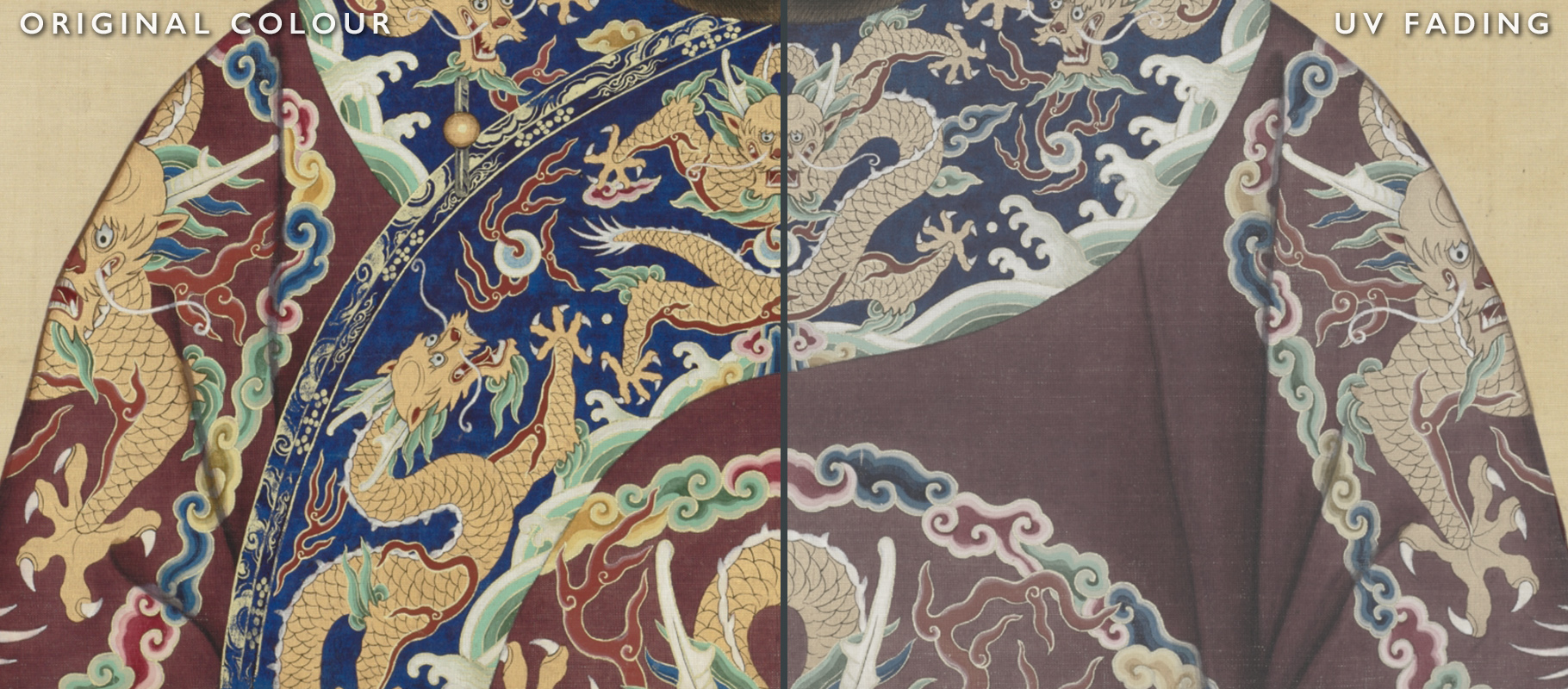

The materials used in ancestral portraiture are sensitive to light, moisture and their overall environment. This makes them susceptible to severe deterioration, colour loss and obscured details due to UV fading or atmospheric disturbances.

Above: scroll painting of Shakyamuni with a heavily discoloured surface, 17th century

Above: scroll painting of Shakyamuni with a heavily discoloured surface, 17th century

The surface of a traditional portrait may be a combination of silk and rice paper – also known as xuan paper. These have been mounted for extra strength, allowing for the scroll to be rolled away. Over time, mounting adhesives may separate and fail or begin to stain the paint layer. Constant or prolonged rolling of a scroll may have also led to severe folds, flaking pigments, and tears.

Although scrolls were originally designed to be put out on display and then rolled away at the end of a festival or event, their age makes this constant movement a high risk procedure. We recommend keeping all artworks flat in storage, with the painted side facing up.

Above: original bright pigments vs the colour fade that can occur when a sensitive artwork is openly exposed to sunlight

Above: original bright pigments vs the colour fade that can occur when a sensitive artwork is openly exposed to sunlight

When on display, ensure the surrounding mount is non-acidic and UV protective glass is in place. For this type of artwork we recommend museum glass or museum acrylic, preventing 99% of UV rays whilst having lessened reflections to allow a clear view of intricate details. Ancestral paintings can be very large and may require a fully bespoke frame, this is something that our team can provide for you – with options to suit any interior.

When a large ancestral painting is framed, the weight may require professional installation to avoid falls from height. Many artworks in our studio come to us after suffering from this type of damage, with glass shards disturbing the delicate surface. Always ensure that the hanging apparatus is secure and strong.

Above: a page from a 19th century family portrait album, staining has occurred at the top of all pages due to moisture

Above: a page from a 19th century family portrait album, staining has occurred at the top of all pages due to moisture

Environmental conditions for Chinese portraits on paper should be monitored, if possible. Avoid areas high in humidity or with high temperatures, as this can severely disturb the materials and attract mould growth. Do not display in direct sunlight, even with UV protection in place, constant changes in temperature and bright exposure should be prevented. Due to various atmospheric pollutants, our team would always recommend that these artworks are displayed safely behind glass.

Above: detail from a portrait of an official with pigment loss and unoriginal retouching, 17th century

Above: detail from a portrait of an official with pigment loss and unoriginal retouching, 17th century

Ancestral portrait restoration

Our team has restored various artworks composed on Asian paper and silk, you can see examples of Chinese panels here and Japanese prints here. The preservation of large scale ancestral portraits is also possible, including the installation of new glazing or the creation of bespoke mounts and framing. All restoration is conducted using precise conservation methods, honouring the historic and artistic integrity of the portrait.

Above: a portrait that was conserved in our studio, before and after sensitive restoration techniques

Above: a portrait that was conserved in our studio, before and after sensitive restoration techniques

Restoration can be a minimal approach, sensitively cleaning the surface and stabilising weak areas. If severe damage is present, our paper conservator can address these with a result that does not affect the historic and artistic integrity of the artwork. Tears, water stains, mould growth and smoke damage can result in devastating visual disturbances – but sensitive treatments can save a portrait from total loss, often with amazing results.

Above: detail from a portrait before and after restoration in our studio

Above: detail from a portrait before and after restoration in our studio

Below is a recent Chinese portrait that was treated by our paper conservator. The surface was cleaned and stabilised, the frame had standard glass replaced with museum quality UV protection.

How can we help?

If you have any questions about art restoration, please do not hesitate to get in touch. As part of our service we offer a nationwide collection and delivery service. E-mail us via [email protected] or call 0207 112 7576 for more information.

Above: detail from a portrait scroll depicting several generations of one family

Above: detail from a portrait scroll depicting several generations of one family Above: imperial portraits of a lady, the Yongzheng Emperor, a Yongzheng Empress and a Qianlong Empress, all from the 19th Century

Above: imperial portraits of a lady, the Yongzheng Emperor, a Yongzheng Empress and a Qianlong Empress, all from the 19th Century Above: detail from a large group portrait, 1796-1820

Above: detail from a large group portrait, 1796-1820 Above: two pages from a family portrait album, mid 19th century

Above: two pages from a family portrait album, mid 19th century Above: details from a portrait of the Qianlong Emperor as a young man, 19th century

Above: details from a portrait of the Qianlong Emperor as a young man, 19th century Above: an embellished portrait that would have been commissioned during the life of the sitter and re-purposed after his death for veneration in an ancestral shrine, late 18th / early 19th century

Above: an embellished portrait that would have been commissioned during the life of the sitter and re-purposed after his death for veneration in an ancestral shrine, late 18th / early 19th century Above: portrait of an old lady (1561-1621), portrait of a husband and wife (late 18th-early 19th century), portrait of the artist’s Great Grand Uncle Yizhai at the age of Eighty-Five (1561-1621)

Above: portrait of an old lady (1561-1621), portrait of a husband and wife (late 18th-early 19th century), portrait of the artist’s Great Grand Uncle Yizhai at the age of Eighty-Five (1561-1621) Above: a portrait of the Qianlong Emperor (centre) and two of his consorts, 1736–70

Above: a portrait of the Qianlong Emperor (centre) and two of his consorts, 1736–70 Above: scroll painting of Shakyamuni with a heavily discoloured surface, 17th century

Above: scroll painting of Shakyamuni with a heavily discoloured surface, 17th century Above: original bright pigments vs the colour fade that can occur when a sensitive artwork is openly exposed to sunlight

Above: original bright pigments vs the colour fade that can occur when a sensitive artwork is openly exposed to sunlight Above: a page from a 19th century family portrait album, staining has occurred at the top of all pages due to moisture

Above: a page from a 19th century family portrait album, staining has occurred at the top of all pages due to moisture Above: detail from a portrait of an official with pigment loss and unoriginal retouching, 17th century

Above: detail from a portrait of an official with pigment loss and unoriginal retouching, 17th century Above: a portrait that was conserved in our studio, before and after sensitive restoration techniques

Above: a portrait that was conserved in our studio, before and after sensitive restoration techniques  Above: detail from a portrait before and after restoration in our studio

Above: detail from a portrait before and after restoration in our studio